Every woman wants to know her risk of breast cancer.

The dread disease kills half a million women worldwide every year, or about 1 percent of women who die each year. Heart disease, lung cancer, liver cancer, stomach cancer, hypertension, H.I.V., diabetes and road injury are much larger killers. But, as Florence Williams points out in her popular book, “Breasts: A Natural and Unnatural History,” the mammary glands have been so thoroughly “feted and fetishized” that many women believe breast cancer poses their greatest mortal threat.

Almost weekly, the media announces a new breast cancer risk fact based on a study associating the disease with a certain substance, behavior or biological characteristic.

Among the many stated risks are smoking, obesity, bad genes and rogue proteins, soft drinks and alcohol, plastics, pesticides, cosmetics, household and industrial chemicals, sugar-induced early menarche, late menopause, hormone replacement therapy, dense breasts, lack of exercise, dairy products, red meat, radiation, mammograms, M.R.I.s, airport scanners, a family history of breast cancer, too much estrogen, affluence, higher education, being white, missing teeth, gum disease, breast implants, not having a child, having a child if black, having a child late in life, having a child early in life, giving birth to a high-weight baby, not breast feeding, diabetes, living in a rural area, dwelling in a city, being lesbian, being tall, watching television, working the night shift, being poor, newly immigrating from a less industrialized place, lack of health insurance, high blood pressure, nasty gut bacteria, getting tested for a genetic mutation, taking multivitamins, not taking multivitamins, taking antibiotics, eating fats in puberty, ingesting folic acid or eating eggs while pregnant, high cholesterol, skin moles, smelly armpits and wet ear wax.

Conversely, exercising regularly; eating walnuts, watercress, apples, broccoli, soy and omega-3 fats; and eating eggs when not pregnant are considered to be protective factors. So are having migraine headaches, performing at least 17 hours a week of housework and having a baby before age 30. (Career women, beware!)

Each item on the risk menu was the subject of published research that found a statistically significant association with the presence of breast cancer in a studied population. But the major risk factor, bar none, is age.

Due to a lifetime of accumulating genetic mutations and soaking up carcinogenic molecules, women over age 65 get the vast majority of breast cancers. Their age accounts for 80 percent of their risk.

Living a healthy life is widely acknowledged as the key to avoiding cancer. But as lifespans increase, so do the probabilities that a stressed cell will make a bid for immortality through unbridled self-reproduction. So why are women afraid of breast cancer in particular? And how are its risks determined?

The complexities of risk

Risk is a measure of uncertainty at a frozen moment in time. It is a probability, a percentage, a guess about the frequency of future events based on information about past events and the assumption that the future will reflect the present.

Risk calculates the strength of links between causes and effects in large groups. Because cancers have multiple interlocking causes, it is difficult to calculate an individual’s risk of breast cancer in a changing world.

Consequently, the risk of cancer is typically described as the annual number of new cases of a disease in large groups. An “incidence rate” is the frequency with which new cases of a disease appear over a period of time. It is simplified as the number of new cases diagnosed each year per 100,000 people at risk of getting the disease.

If correctly reported to a cancer registry, rising and falling incidence rates can track the virulence of a disease in a population. When comparing disease incidence between populations, rates are formulaically adjusted to account for differences in the average age of the compared groups.

The usual practice for describing the risk of breast cancer to a concerned woman is to cite the incidence rates for populations that include her personal characteristics, such as age, genetic peculiarities, race, socioeconomic factors and her place of work or residence. For a small sub-population—women over 40 in Marin County, for example—the actual number of new breast cancer cases is multiplied to fit a hypothetical population of 100,000 women over 40.

(In Marin there are less than 65,000 women over age 40, so the actual count of their cancer diagnoses will be about 35 percent less than the extrapolated incidence rate numbers.)

Epidemiologists talk about incidence rates to give people a rough sense of their potential exposure to a disease. Importantly, incidence rates are not the same as “lifetime risk,” which applies to all women, regardless of personal characteristics. The familiar claim that in the United States and Europe “one out of eight women will get breast cancer during their lifetimes” powers the heart of the many fundraising pitches mounted by foundations and corporations that “fight” breast cancer. Journalists, scientists, activists and politicians echo the slogan without questioning how it was derived.

As a result, many women incorrectly assume that in a group of eight women, at any given moment, one person is tagged with a deadly, invisible “C.”

To understand what lifetime risk means, I visited Patricia Kelly in her magically gardened Berkeley home. Dr. Kelly is a medical geneticist specializing in cancer risk assessment. Now retired, she has served as the director of cancer risk analysis at a number of Bay Area hospitals. She has published technical and popular books about how to assess breast cancer risk.

Sipping herbal tea in a sunny alcove, Dr. Kelly explained the “one in eight” slogan with a traveling metaphor: Envisage her living on a mountain top at the end of a narrow, winding road flanked by 1,000-foot cliffs that have taken lives. If the risk that I will drive off the road to my death when I visit her is 2 percent, then when I arrive at the top I can subtract 1 percent of the risk. As I head back down again, the risk decreases by each succeeding mile until I reach the flatlands with a sigh of relief.

It is the same with the lifetime risk of breast cancer—which is not the same thing as a woman’s risk at any specific age.

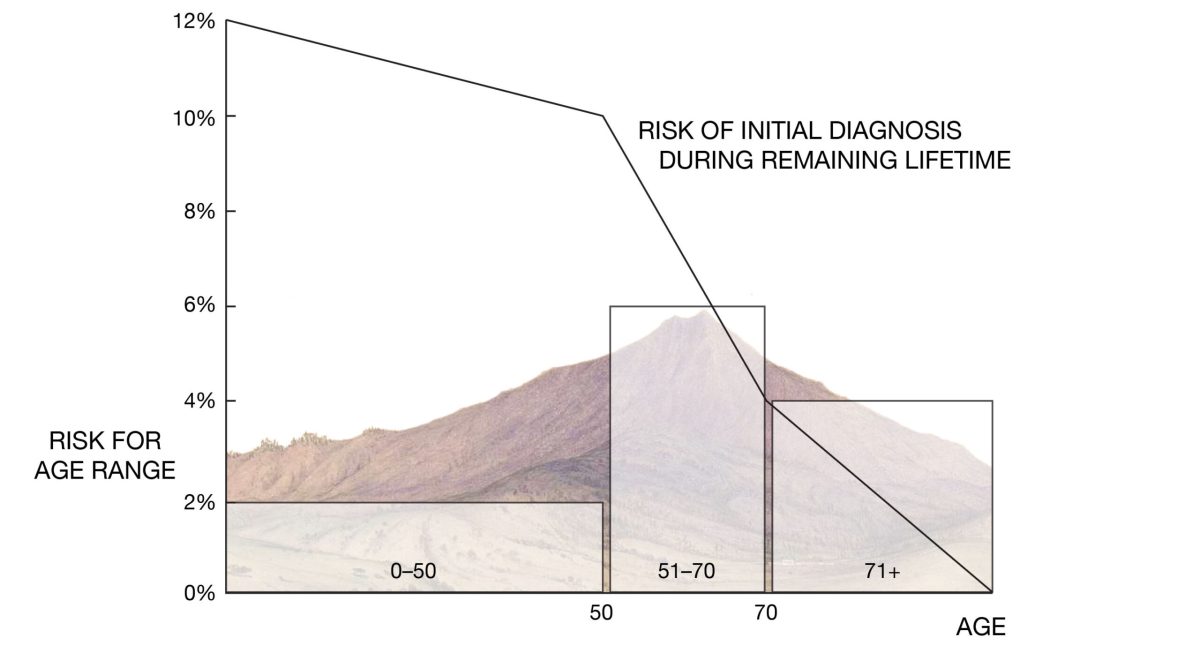

A newborn girl enters the world with a 12 percent lifetime risk of being diagnosed with breast cancer, assuming that she will live to age 100. Every passing year, her lifetime risk decreases, even though as she ages she is more likely to be diagnosed, because cancer is primarily a disease of upper middle age. The “one in eight” slogan fails to capture this important fact.

It may be more helpful for individuals to understand their risk at a given age. The risk of breast cancer from birth until age 50 is 2 percent, meaning that two out of 100 women who live until age 50 will be diagnosed (or overdiagnosed). By age 50, the lifetime risk remaining is reduced to 10 percent (12 percent at birth minus 2 percent for living to age 50).

From age 50 to 70, a woman has a 6 percent chance of being diagnosed with breast cancer; these 20 years are the period of greatest risk. Still, the annual risk to the average woman in that group is only three-tenths of 1 percent. In other words, her chance of not getting a breast cancer diagnosis each year is 99.7 percent.

After 70, the lifetime risk of a breast cancer diagnosis drops precipitously, as other infirmities claim lives.

And those who die from breast cancer are far fewer than those diagnosed with it: five out of 1,000 women between ages 50 and 74 over the span of a decade, according to the National Cancer Institute. (The lifetime risk of dying from breast cancer is about 3 percent.)

During her decades-long clinical career, Dr. Kelly counseled hundreds of women about their risks and treatment options. She recalled: “Doctors sometimes were upset when, after hearing the risks I presented, their patients decided not to have a mastectomy.” Unfortunately, many doctors do not understand the ins and outs of cancer risk. For Dr. Kelly, the concept of risk needs to be taught better in medical schools. She also questions the conclusions of studies purporting to show that wealthy white women in Marin and similar communities get more breast cancer. She said these studies persist in influencing the public because reporters, like many medical practitioners, do not understand the difference between “absolute risk” and “relative risk.”

Absolute and relative risk

Consider an increase from two to three cases in 100,000 women. The absolute risk increase is almost zero—one case in a population of 100,000—but the relative risk is an increase of 50 percent. Relative risk is often what is cited in medical literature and news articles, with alarming effects.

In 2004, using relative risk, the Cancer Prevention Institute of California reported the five-year average incidence rate of invasive breast cancer for white women in the Bay Area. The institute said the Marin rate was 6 percent higher than the Bay Area incidence rate and 15 percent higher than the California rate.

As Dr. Kelly points out, this way of framing the data obscures the fact that the difference in absolute risk between the county and regional rates was so small as to be practically meaningless.

Let’s look at how these risks are calculated. The five-year average of breast cancer incidence rates for white women in Marin from 1997 to 2001 was 176 cases per 100,000 women. The average number of cases in the Bay Area was 165; in California, it was 154.

These averages have numerically wide “confidence levels,” or margins for error, so the real figures could be 10 or more points in either direction. Because it is a small county, the error margin for the Marin incidence rate is spread over 20 points. (The margin for California varied by a mere two points because it is a much larger population.)

Using the averages, the difference in absolute risk between Marin and the Bay Area was one hundredth of 1 percent, or 11/100,000. The difference between the Marin and California averages was two hundredths of 1 percent.

Such tiny absolute differences can easily arise from the poor quality of cancer registry data—or, to be only slightly facetious, from the delayed effects of a butterfly wing flapping in Borneo a million years ago.

This is not to downplay the tragedy that nearly 24,000 women in California were diagnosed with breast cancer in 2010. Nevertheless, that figure is a tiny fraction of 1 percent of the 19 million women in the state. An individual woman’s risk is equally small.

Using the most recent cancer registry data, let’s see how breast cancer incidence numbers for Marin stack up over the long haul. From 1988 to 2012, Marin averaged 154 new cases per 100,000 women; California averaged 127, for a difference of 27 cases. The absolute rate for the difference is 27/100,000, or nearly three one-hundredths of 1 percent.

Yet the relative rate is 21 percent higher for Marin.

It’s easy to see that casting differences as relative rates serves far better as media bait than as an accurate depiction of risk.

Marin’s annual breast cancer death count, in real numbers, has fallen steadily from 51 deaths in 1988 to 31 in 2013. If there had been an epidemic, those rates would have increased, not decreased.

But the absence of a cancer cluster is not a news story.

Dr. Kelly spent her career explaining breast cancer risk so that women could make informed decisions under the stress of a new diagnosis.

“All over the country, it is the upper-class women who are more often diagnosed with breast cancer because they are more likely to have access to medical care,” she said. “Every day is precious, but many of my patients seemed to think that if they did not die of breast cancer, they would live forever.”

Cancer Cluster Busters?

In November 2012 the San Francisco Chronicle reported on a study about the spread of breast cancer among wealthy white women. The article, titled “Bay Area Cancer Clusters Seen, Marin Not Only Spot in Area With Higher Rate of Disease” told the story of a California breast cancer mapping project funded by the University of California and the state Department of Public Health. The Cancer Prevention Institute of California provided data and researchers, and an advisory group included local breast cancer activists.

The project authors declared that, “The elevated rate of invasive breast cancer among women living in Marin County has been well documented. The findings in this report, however, raise the possibility that communities elsewhere … may be similarly affected.”

The terrifying claim of newly discovered cancer clusters was presented in terms of relative, not absolute, rates. The authors found that from 2000 to 2008, Marin and other communities of affluent women in California had the highest invasive breast cancer incidence rates—as much as 29 percent higher than the state average.

But the absolute numbers buried in the study tell a different tale. The data for the North Bay show 112 cases per 100,000 women, versus 95 cases per 100,000 for the rest of California. The difference is 17 cases in 100,000 women—or 17/100s of 1 percent. The South Bay clocked in at a numerator of 123 cases, for a difference from the rest of California of 28 cases, or 28/100s of 1 percent.

By framing these minute differences as relative ratios of 17 percent and 29 percent, the authors obscured the statistical insignificance of the quantum-sized increase—a difference that can be accounted for by chance or by more frequent screening.

According to California Health Interview Survey, 78 percent of upper middle-class white women in the South Bay get regular mammograms, compared to 65 percent of Californians. More screening means more new diagnoses and higher incident rates, but the study did not explore this explanation.

Instead, launching a circular argument, it claimed that the finding that white women had more cancer “was consistent with the fact that White [sic] women face an increased rate of breast cancer.” The study also claimed that the low incidence rates for Latinas are “consistent with the fact that Hispanic women face a decreased risk of breast cancer.”

The California Health Interview Survey reports that Latinas get significantly fewer mammograms than do wealthy white women—and their breast cancer death rates are rising. The breast cancer mortality rate for African Americans is much higher than for whites in California, although blacks have less access to screening and medical care.

Read part one here: https://www.ptreyeslight.com/article/busted-breast-cancer-money-and-media-part-one-renee-willards-story

Read part three here: https://www.ptreyeslight.com/article/busted-breast-cancer-money-and-media-part-three-marin-syndrome

Read part four here: https://www.ptreyeslight.com/article/busted-breast-cancer-money-and-media-part-four-canary-gold-mine

Read part five here: https://www.ptreyeslight.com/article/busted-breast-cancer-money-and-media-part-five-does-hormone-replacement-therapy-cause-breast

Read part six here: https://www.ptreyeslight.com/article/busted-breast-cancer-money-and-media-part-six-perils-mammography

Read part seven here: https://www.ptreyeslight.com/article/busted-breast-cancer-money-and-media-part-seven-life-and-death-marin-womens-study

Read part eight here: https://www.ptreyeslight.com/article/busted-breast-cancer-money-and-media-part-eight-how-zero-breast-cancer-pays-its-bills

Read part nine here: https://www.ptreyeslight.com/article/busted-breast-cancer-money-and-media-part-9a-bad-data-dirty-laundry

Read part ten here: https://www.ptreyeslight.com/article/busted-breast-cancer-money-and-media-part-ten-bad-data-audit-trail

Read part eleven here: https://www.ptreyeslight.com/article/busted-breast-cancer-money-and-media-part-eleven-story-abigail-adams-how-california-cancer