As fears of a Marin-centric breast cancer epidemic among educated, high-income white women spread in the late 1990s, the Marin County Department of Health and Human Services assigned its maternal and child health care coordinator, Rochelle Ereman, to direct its epidemiological response to the problem.

Ms. Ereman has a master’s degree in public health from the University of California, Berkeley. She supervises a small team of county epidemiologists who regularly collaborate with the advocacy group Zero Breast Cancer and cancer research groups in the Bay Area.

To supplement the epidemiologists’ general fund salaries and to pay for research activities, the county has sought outside funding.

Despite the Centers for Disease Control’s own findings that the elevated incidence rates of breast cancer in Marin are an artifact of above-average mammography screening rates, the federal agency has granted the county $2 million to search for a cause of the cancer cluster. The California Department of Public Health has kicked in $500,000 and the Avon Foundation for Women has donated $1.3 million since 2007, along with nearly $1 million to support Zero Breast Cancer’s participation.

The brands of the Avon Foundation and Avon Products, Inc. are interwoven with a pink ribbon. One of the world’s largest cosmetics companies, Avon’s six million door-to-door saleswomen and retail outlets book $9 billion a year, a portion of which finds its way to funding breast cancer research and promoting screening mammography.

The money from Avon funded the Marin Women’s Study, which has collected mammographic data and saliva-based DNA samples from thousands of Marin women, mostly white and insured.

Using that data, Ms. Ereman and her collaborators have published studies that associate both the use of hormone replacement therapy and not having children to an increased risk of breast cancer.

From the beginning, the county health department was focused on searching the lifestyles of affluent white women for causes of breast cancer. Its scientists have acknowledged that the county’s above-average screening rates could account for much of the elevated incidence rates, but they have chosen not to develop that theory.

The white map

In 2000, the C.D.C. funded the creation of a Bay Area task force “to evaluate the high and increasing incidence of breast cancer in Marin County.” Directed by Ms. Ereman, it included Christopher Benz from the Buck Institute on Aging, Christina Clarke from the Cancer Prevention Institute, a roster of Ph.Ds. from the University of California, local oncologists and surgeons and a half-dozen community activists.

The committee’s first task was to create a geographic map of white women’s place of residence at the time of their breast cancer diagnoses from 1988 to 1992.

“Because there are few non-white women living in Marin County, we did not calculate ratios for other races,” the task force reported.

The county health department’s oft-stated position is that non-white women residing in Marin are so few as to be statistically insignificant. But according to the United States Census Bureau, non-whites—including Latinos—were nearly a quarter of the county population in 2000, up from about 20 percent in 1990. In 2013, non-whites were 27 percent and rising.

Needless to say, non-white women also die from breast cancer. In fact, 10 percent of the county’s breast cancer diagnoses since 1988 have been for non-white women, who also suffer 7 percent of the county’s total deaths from the disease. These are not insignificant numbers.

The racial bias of the white map guided the design of the Marin Women’s Study.

Design flaws

The study, which surveyed 14,000 women from 2006 to 2010, was based upon two premises. First, that highly educated, wealthy white women get more breast cancer, and second, that the excess of disease can be caused by their lifestyle—supposedly some combination of drinking too much alcohol, delaying or forgoing motherhood and ingesting estrogen to combat the symptoms of menopause.

But mortality rates indicate that non-white women in America are significantly more likely to die from breast cancer than are white women, who tend to have more access to better medical care, including screening. These services elevate incidence rates for whites, who do not get more breast cancer.

On the other hand, women without private health insurance tend to delay seeking treatment until symptoms become apparent; they are also screened less frequently, resulting in fewer diagnoses and lower incidence rates.

The Marin Women’s Study was not a randomized clinical trial, the gold standard of medical research because it is designed to remove bias. Rather, it was what’s known as an “ecological” study, and as such it contained built-in biases.

One was the assumption that excess screening does not account for excess incidence.

The study’s 81-question survey starts with the multiple-choice question, “What do you think is causing the high breast cancer rates in Marin County?” There were five answer bubbles, none of them about the effect of screening.

The survey asked about use of birth control and hormone replacement therapy; consumption of alcohol, organic food and raw milk; proximity to pet flea collars; and exposure to pig hooves. It did not ask a single question about cosmetics or personal-care products, which often contain suspected carcinogens.

It did ask for a “racial” identification, followed by, “Do you have Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry?” (Mutated BRCA genes carried by some Ashkenazi are associated with increased breast cancer risk.) The survey did not single out any other ancestries, even though all women, especially black women, can carry mutated BRCA genes.

In addition, the exclusion of data from non-white women from the project’s core studies left a deep rift in its efficacy. While non-whites did not fully participate proportionate to their share of the county population, the data of those who did was excluded for so-called genetic reasons.

In an interview with the Light about the exclusion of non-whites from studies of the Marin Women’s Study data, the county’s public health officer, Matt Willis, explained that the racially selective health department studies “do not want to mix populations with intrinsic genetic differences.”

It was an odd statement, since the Human Genome Project—an international collaboration completed in 2003—revealed that ancestry, not “race,” which is a social construct, is the predictor for genetic differences that may affect susceptibility to chronic disease.

Nor are whites genetically monolithic. There is greater genetic diversity between members of a single race than between the various waves of people migrating out of Africa during the past 100,000 years.

Many blacks and Latinos also have European ancestry, just as many whites have black and Latino ancestry. And the definition of “white,” as used by the California Cancer Registry, ranges from Norwegian and Russian to Afghani and Zoroastrian.

In addition, many of the so-called non-white women in Marin, including Asians, share the same basic educational and income profiles and lifestyle behaviors as their white neighbors. Not all black and Latina women are poor, and not all white women are rich. But they all get breast cancer.

Separating whites from non-whites in studies searching for causes of breast cancer in a geographic region is a kind of scientific apartheid, an artificially induced separation based on social constructs and politics, not on science.

Pressed about this charged issue, Dr. Willis remarked, “Nobody would have published anything that we wrote if we had not separated the races.”

The Light pointed out that the problem was that non-whites were largely excluded from the epidemiological agenda, despite their higher breast cancer mortality rates.

Dr. Willis took a deep breath. “Your story is going to help us as a society move forward in terms of our understanding of breast cancer,” he said. “The reason things change is because people ask questions. History is made through people pushing.”

The study’s fruits

In 2010, Dr. Clarke of the Cancer Prevention Institute, Dr. Benz of the Buck Institute and the county’s epidemiologists teamed up with a Zero Breast Cancer activist and published the results of their first analysis of the data gathered by the Marin Women’s Study.

The study was titled “Recent trends in hormone therapy utilization and breast cancer incidence rates in the high incidence population of Marin County, California.”

It began by noting that the county “has received media and research attention due to high breast cancer rates.” It went on to claim—erroneously—that the breast cancer incidence rate for white women in Marin had been 38 percent higher than the California average in the late 1990s.

The authors failed to note that the 38 percent figure had already been downgraded to 15 percent after the discovery of research errors.

The study analyzed data from 1,083 white women over age 50. On the basis of race alone, it excluded data collected from 171 non-white women who met the study criteria.

These women would have composed 15 percent of the data sample, and the information they brought could have changed or broadened the results.

The authors presented an elaborate theory to explain the alleged cancer cluster, based on the assumption that an anomalous drop in breast cancer incidence in Marin in 2003 was due to women quitting a hormone replacement drug called Prempro the previous year.

(As we learned in the fifth installment of this series, in 2002 a clinical study on Prempro was terminated out of fear that the drug caused breast cancer, prompting a sudden drop in use. A tiny drop in incidence rates in 2003 led some researchers, including at the Cancer Prevention Institute, to suggest that the Prempro had “promoted” breast cancer and that going off it caused cancers to regress.)

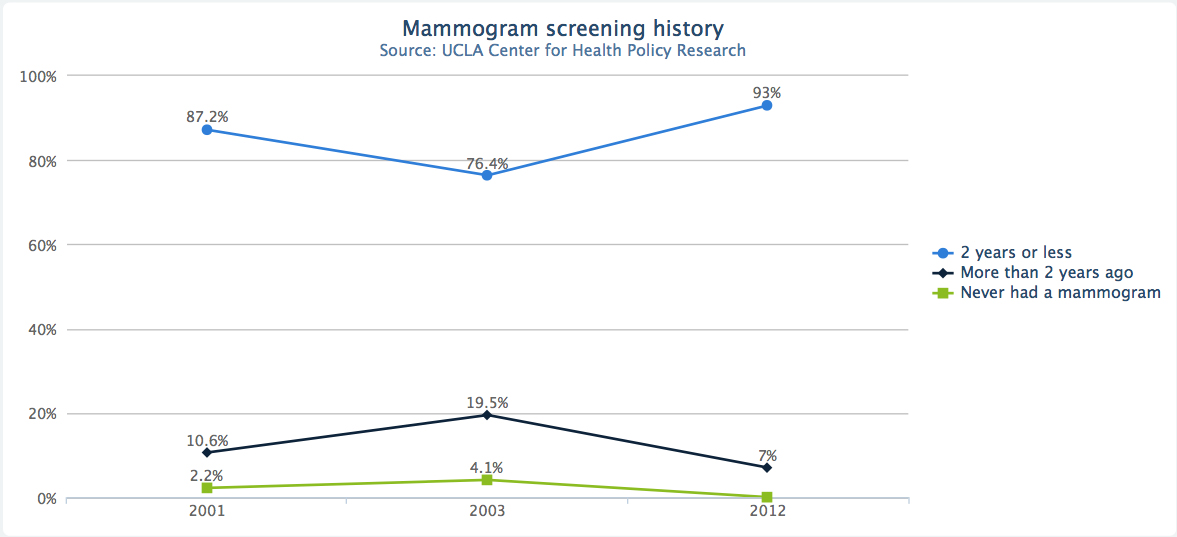

The “Recent Trends” study acknowledged that a drop in screening rates in 2003 could explain the drop in incidence, but it discounted that possibility by cherry-picking data from the California Health Interview Survey.

That data showed a flat utilization of mammography by women statewide from 2001 to 2005; what the researchers didn’t note, however, was that in 2003 there was a large drop in screening rates, not only in Marin, but throughout California and the country.

In Marin, the rate of screening for white women over 50 dropped by 11 percentage points from 2001 to 2003; it dropped by 5.6 percentage points for whites of all ages. San Francisco dropped an incredible 16 percentage points for all whites. The precipitous dips started to rebound in 2005.

So a basic premise of “Recent Trends”—that a drop in screening rates could not explain the drop in incidence rates—is contradicted by data the authors chose to ignore.

Dr. Willis, the county health officer, declined to comment on why the data was bypassed.

When the study was published, the county health department widely disseminated its findings. The local and national media obligingly reported that the Marin breast cancer cluster was caused by hormone replacement therapy.

Cornelia Baines of the University of Toronto is a leading expert in breast cancer epidemiology. At the Light’s request, Dr. Baines reviewed the scientific methodology used by “Recent Trends.” She responded by email, “The paper is yet another one demonstrating poor sample selection—the process is not even clearly described, but clearly suffers from selection bias.” (Selection bias means the data did not represent the population the study purported to examine.)

Dr. Baines observed, “Huge amount of work, but as the saying goes, ‘Garbage in, garbage out.’”

In 2014, county breast cancer researchers and Marc Hurlbert, the director of research at the Avon Foundation who had authorized funding the Marin Women’s Study, published a study based on DNA in saliva contributed by women who had mammograms.

“First Pregnancy Events and future breast density” associated women’s anecdotal memories of their first pregnancy with a measure of their current breast density and a laboratory analysis of their DNA.

A quick primer on breast density. The more milk ducts and lobules a women’s breasts have relative to fat, the denser her breasts. Nearly half of all women, mostly younger, are considered to have dense breasts; density decreases with age.

Density is not known to cause breast cancer, but because mammographic X-rays are more easily blocked by dense breasts, a higher rate of diagnostic uncertainty is associated with greater density.

According to the “First Pregnancy” authors, “research has suggested” that dense breasts are not just associated to breast cancer risk, but are “causal” of breast cancer.

It is almost unheard of for an epidemiological paper to posit causation without presenting strong physical evidence of a linkage, such as the presence of cholera germs in water ingested by cholera victims.

Lacking this type of physical evidence, the study attempted to genetically correlate a high level of pregnancy-induced hypertension during a first pregnancy with lower breast density later in life. The speculation was that pregnancy-induced hypertension (high blood pressure) lowered breast density, which in turn lowered the risk of breast cancer.

In other words, having hypertension during pregnancy could be protective against breast cancer.

Of course, pregnancy-induced hypertension can be very dangerous in its own right, speculations about cancer risk aside.

The authors cautioned that their complicated theory of possible causation, based on examining a small subset of the saliva samples, could be completely wrong due to chance and biases in how the sample was selected. They also noted that other scientists have shown that pregnancy-induced hypertension increases the risk of breast cancer.

Further undermining their hypothesis was the fact that only about half of the women who participated in the project donated the requested two teaspoons of saliva samples. The spit was collected after an eight-hour fast “upon awakening and before brushing or flossing their teeth” and mailed in a postage-paid plastic envelope.

It later turned out the samples could not be guaranteed to be free from contamination by bacterial DNA and of research quality.

Another problem with the theory is that since breast density decreases with age, regardless of prior pregnancy health, there is no way to separate the normal effects of aging from the possibility of pregnancy-induced hypertension on breast density later in life.

Nor did the scientists possess a measure of their subjects’ breast density before they gave birth the first time, so they could not know if their density level had changed.

Nevertheless, the county health department issued a statement claiming that the density-based study “confirmed” that delayed childbirth increases breast cancer risk.

That same year, 2014, Marin’s breast cancer team published a paper on how to assess a Marin woman’s risk of breast cancer using different predictive models. This effort aimed to associate increased breast cancer risk to never having children or to giving birth after age 30.

The authors warned that the study was epidemiologically limited because it did not apply to the population at large. It also assumed that giving birth for the first time after age 30 is known to increase breast cancer risk, which is certainly not proven.

State health department vital statistics reveal that women in Marin under age 30 have proportionately fewer live births per year than Californians under 30. On the other hand, the 2009 California Health Interview Survey reports that Marin women gave birth more than the California average. The county is historically fecund (the survey has not published birth data from after 2009).

Nonetheless, the authors concluded, “Many women are delaying childbirth for personal, career, and financial reasons, placing them at greater risk of breast cancer.”

In fact, the raw data on the white women with invasive breast cancer who joined the Marin Women’s Study shows that 64 percent gave birth for the first time under age 30—which contradicts the health department’s refrain that delaying or foregoing childbirth increases the risk of breast cancer. This does not mean that having children before age 30 is riskier, just that the data collected by the Marin Women’s Study is unreliable as a measure of reality.

The death of the study

When the C.D.C. and Avon grants ran out, Ms. Ereman applied for more Avon money to continue the Marin Women’s Study. She told funders that the collaborative wished to pursue a genetic analysis of the saliva of white women only.

Her prior intention to explore the oral microbiome was not possible because the collected saliva was poorly preserved and subject to contamination from external bacteria.

This time, she proposed to study the correlation of breast cancer risk to the levels of cadmium and Biphenyl-A in white women’s saliva (which, unlike bacteria, are inorganic).

Cadmium is a suspected carcinogen used in the manufacture of cosmetics, including lipstick. Avon declined to offer any further funding to Ms. Ereman’s team.

“The Avon funding happened to end at the point we gave Avon a proposal on the cadmium pilot project,” Dr. Benz told the Light. He said the two events were causally unrelated.

Proposals to fund more studies of the 8,500 saliva samples—stored in a Buck Institute freezer—have also been rejected, based on the small sample size.

In 2013, the county health department reported the good news that the breast cancer incidence rate for white women in Marin had dropped to 144 per 100,000, a number roughly equal to that for whites in the rest of California. Twelve counties in California now have higher rates than Marin’s; the highest is Yolo County, with 161.

Asked why Marin rates are now normal, Ms. Ereman and Dr. Benz say the elevated rates were caused by the use of hormone replacement therapy. Neither would comment on evidence that the county’s historically high breast cancer incidence rates could have been caused by high screening rates.

Last spring, members of the breast cancer team created an Indigogo campaign to raise $400,000 to continue its aborted work on the saliva samples. It timed out at $11,451.

More surprising than the death of the Marin Women’s Study is the fact that it was even launched in the first place. Public records obtained from the county reveal harsh peer reviews of the original funding application to the Centers for Disease Control.

One reviewer complained, “It is unclear to this reviewer exactly what the ‘breast cancer’ problem is because the application fails to describe whether the increased breast cancer in the county is an increase in incidence or mortality … as there are no actual statistics presented.”

The reviewer went on, “There are individual variables that the investigators want to explore that are not proven risk factors such as alcohol consumption. … Ereman does not appear to be adequately educated, trained and experienced to manage this type of breast cancer study.”

Another wrote that the application was “weak in scientific justification.” “There is not a review of literature to support the examination of specific factors related to behavior, environment or biology as it relates to breast cancer risk,” that person wrote. “There were also no scientific references in the application at all…”

The negative peer reviews could not possibly have inspired confidence in the agency’s funding committee, but legislation sponsored by Senator Barbara Boxer and Congresswoman Lynn Woolsey directed the agency to issue the grant.

Next week, “Busted!” unveils how the Avon Foundation took control of science in Marin.

Read part one here: https://www.ptreyeslight.com/article/busted-breast-cancer-money-and-media-part-one-renee-willards-story

Read part two here: https://www.ptreyeslight.com/article/busted-breast-cancer-money-and-media-part-two-climbing-risk-mountain

Read part three here: https://www.ptreyeslight.com/article/busted-breast-cancer-money-and-media-part-three-marin-syndrome

Read part four here: https://www.ptreyeslight.com/article/busted-breast-cancer-money-and-media-part-four-canary-gold-mine

Read part five here: https://www.ptreyeslight.com/article/busted-breast-cancer-money-and-media-part-five-does-hormone-replacement-therapy-cause-breast

Read part six here: https://www.ptreyeslight.com/article/busted-breast-cancer-money-and-media-part-six-perils-mammography

Read part eight here: https://www.ptreyeslight.com/article/busted-breast-cancer-money-and-media-part-eight-how-zero-breast-cancer-pays-its-bills

Read part nine here: https://www.ptreyeslight.com/article/busted-breast-cancer-money-and-media-part-9a-bad-data-dirty-laundry

Read part ten here: https://www.ptreyeslight.com/article/busted-breast-cancer-money-and-media-part-ten-bad-data-audit-trail

Read part eleven here: https://www.ptreyeslight.com/article/busted-breast-cancer-money-and-media-part-eleven-story-abigail-adams-how-california-cancer