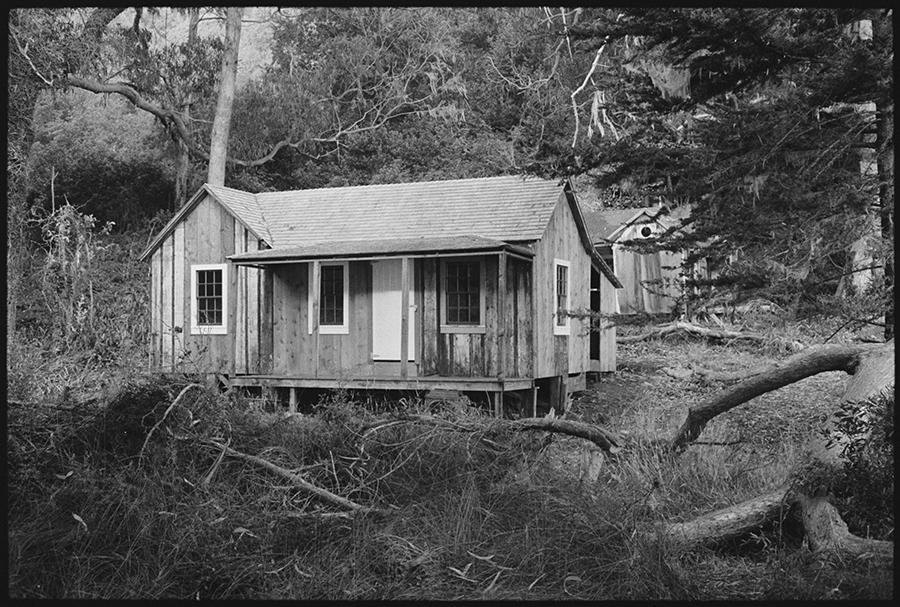

A restoration is underway at Lairds Landing, a remote spot on the western shore of Tomales Bay that teems with local history.

A restoration is underway at Lairds Landing, a remote spot on the western shore of Tomales Bay that teems with local history.