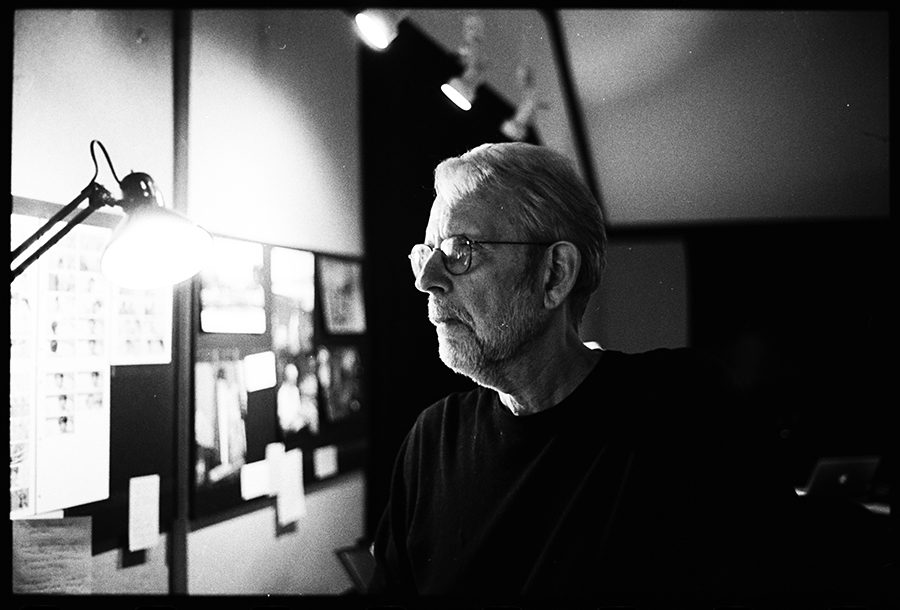

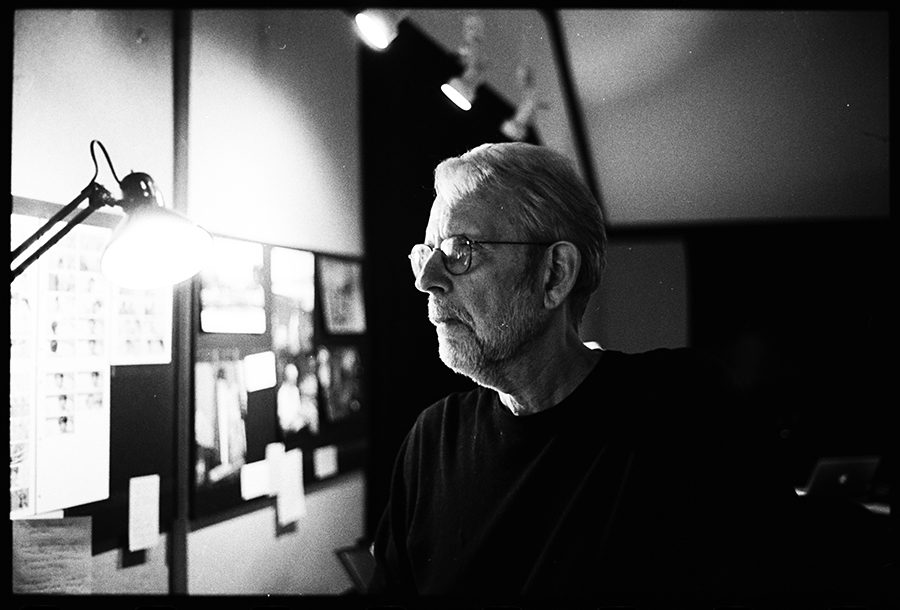

Walter Murch’s job is to make sure you don’t notice his work, practicing the invisible art of sound and film editing, or . . .

Q&A: Film editor Walter Murch explores the science and art of physics

Walter Murch’s job is to make sure you don’t notice his work, practicing the invisible art of sound and film editing, or . . .