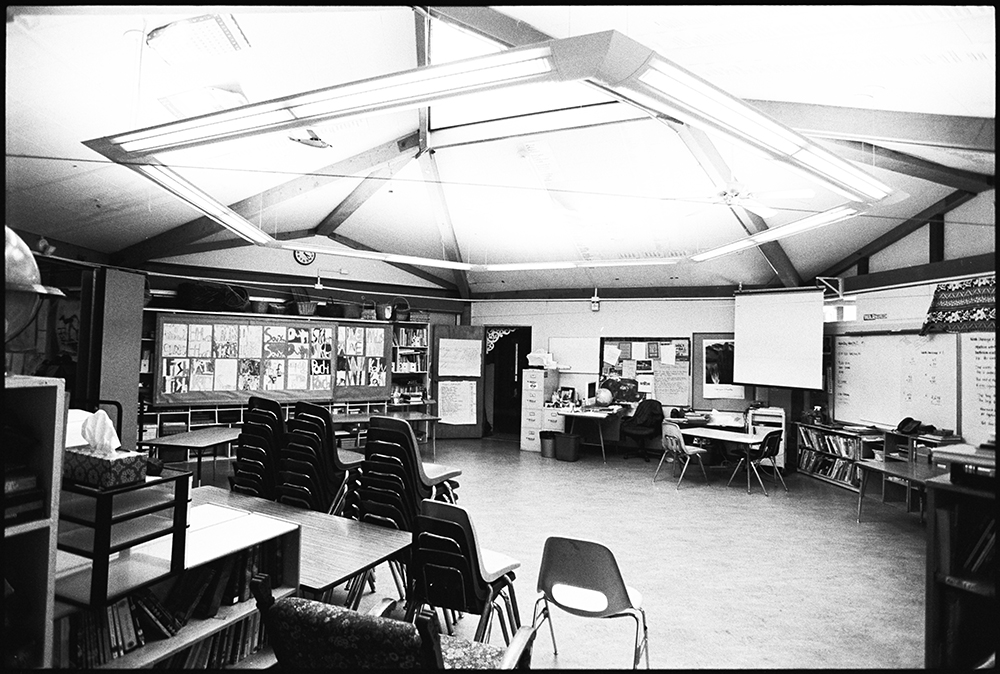

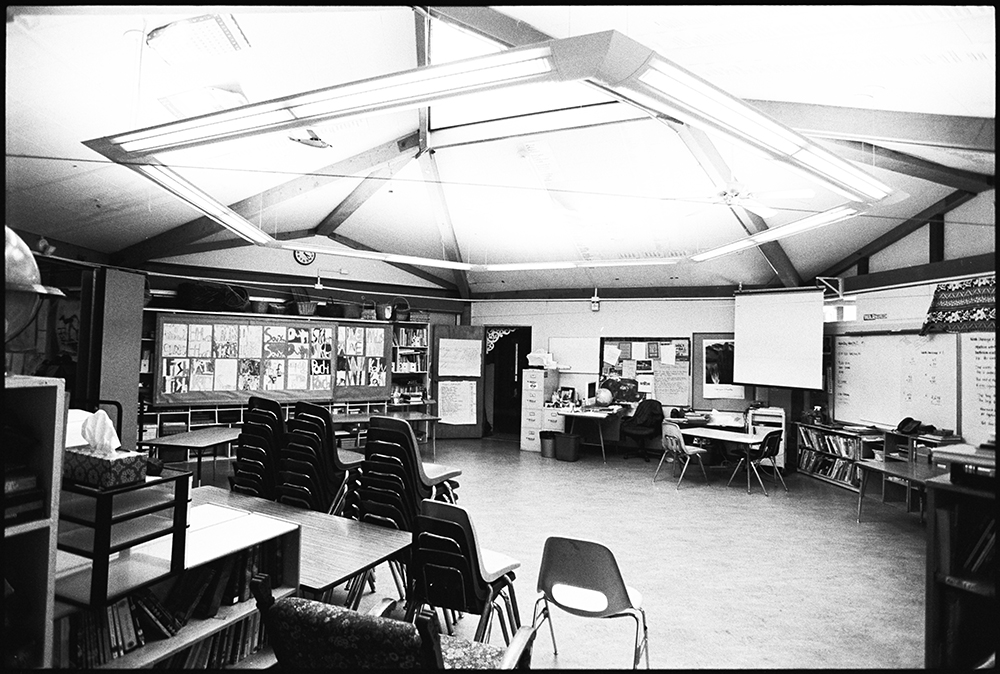

The Lagunitas School District’s Open Classroom program has reached an impasse over whether or not to install sliding doors between classrooms in its . . .

Open Classroom at impasse over doors

The Lagunitas School District’s Open Classroom program has reached an impasse over whether or not to install sliding doors between classrooms in its . . .