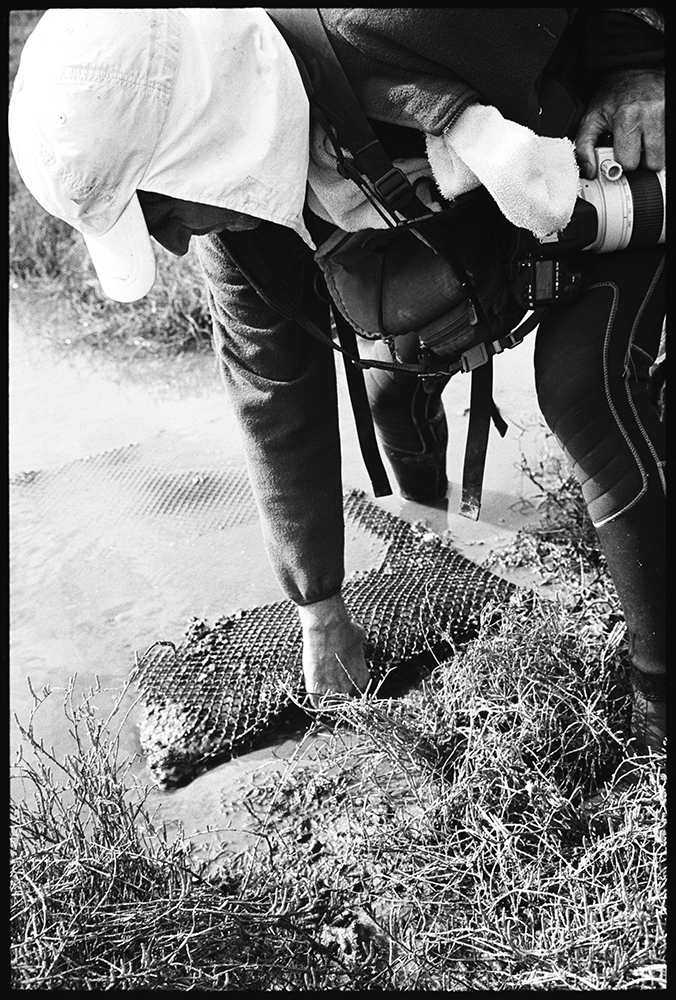

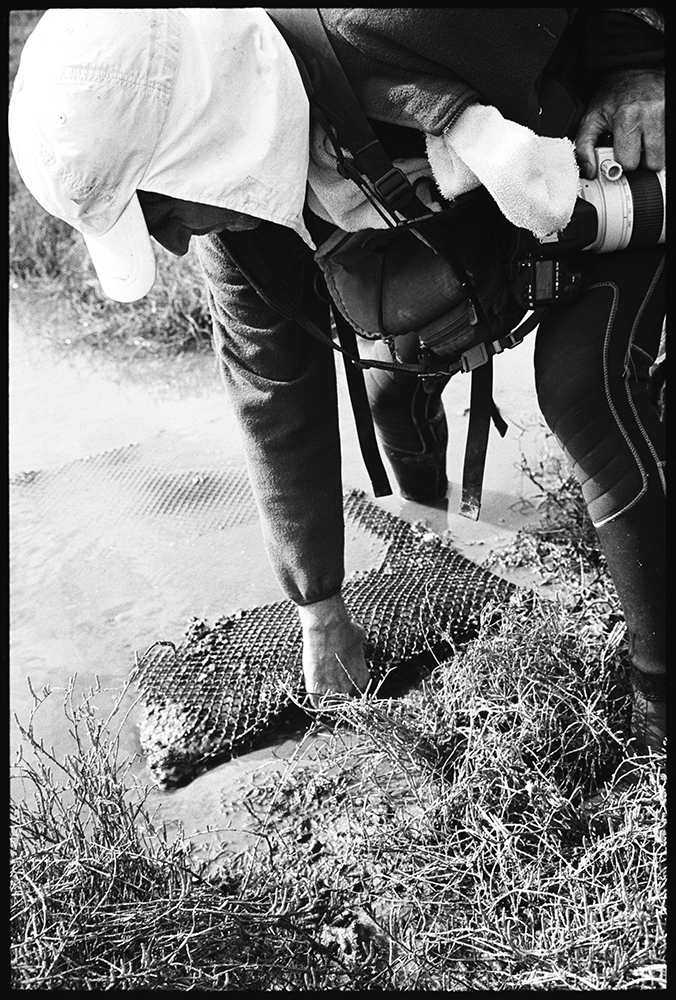

From his old silver Prius parked on the side of Highway One, Richard James pulls out oyster-growing gear he has collected from Tomales . . .

One man’s efforts may change oystering on bay

From his old silver Prius parked on the side of Highway One, Richard James pulls out oyster-growing gear he has collected from Tomales . . .