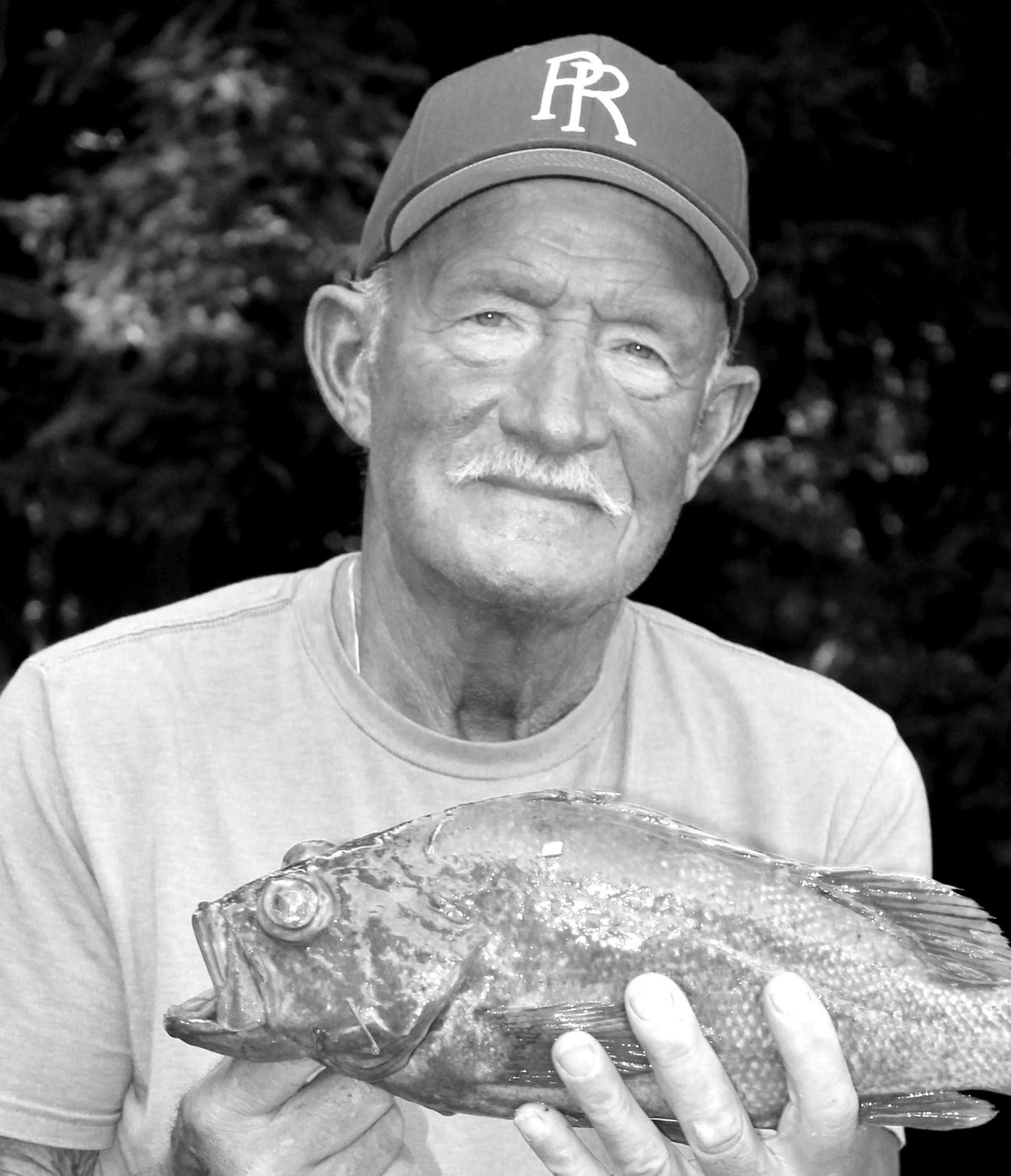

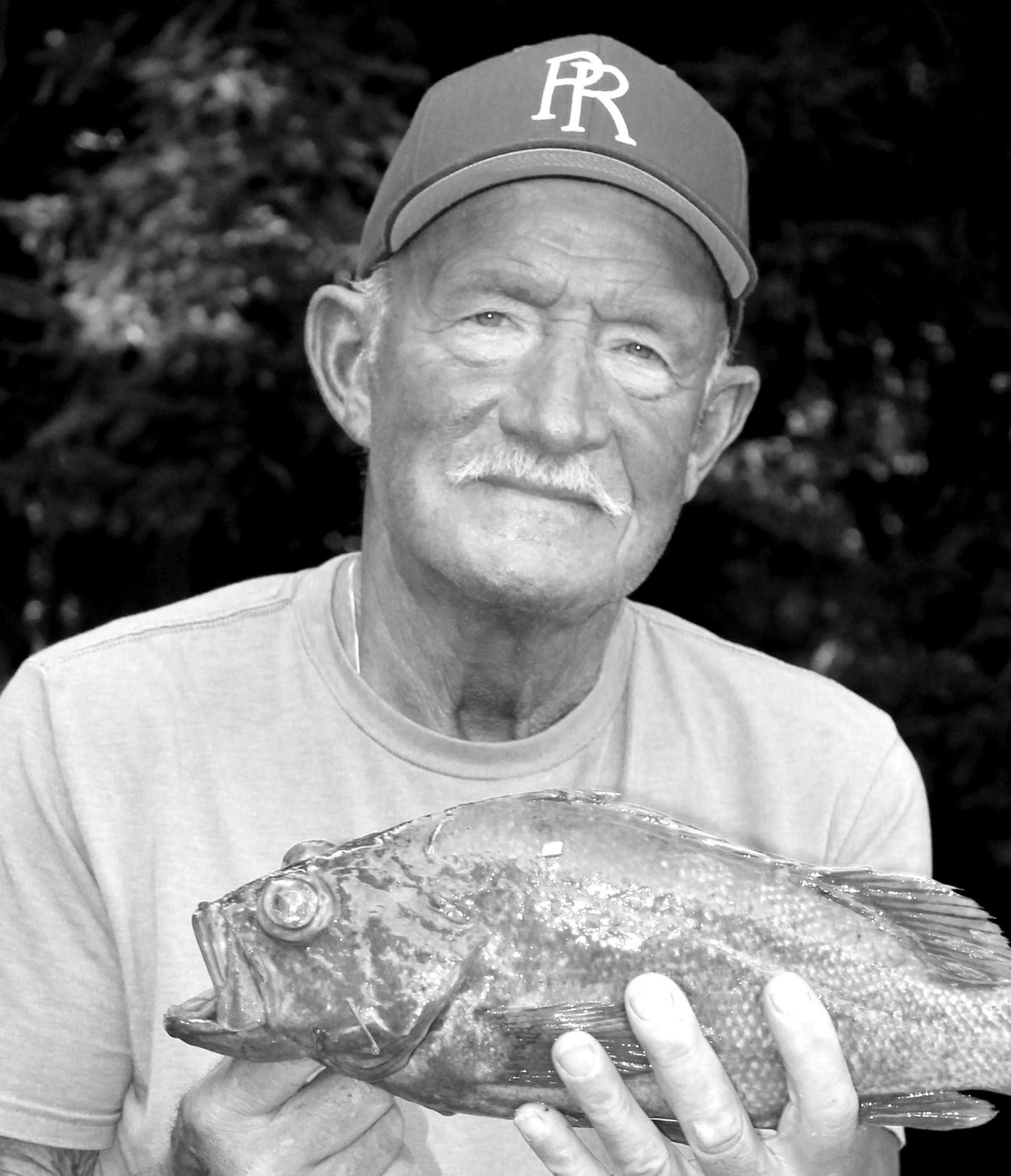

Marty Medin, a fireman and 56-year West Marin resident known for his generosity and knack for fishing, died in Petaluma on July 9 . . .

Marty Medin, fireman and fisherman

Marty Medin, a fireman and 56-year West Marin resident known for his generosity and knack for fishing, died in Petaluma on July 9 . . .