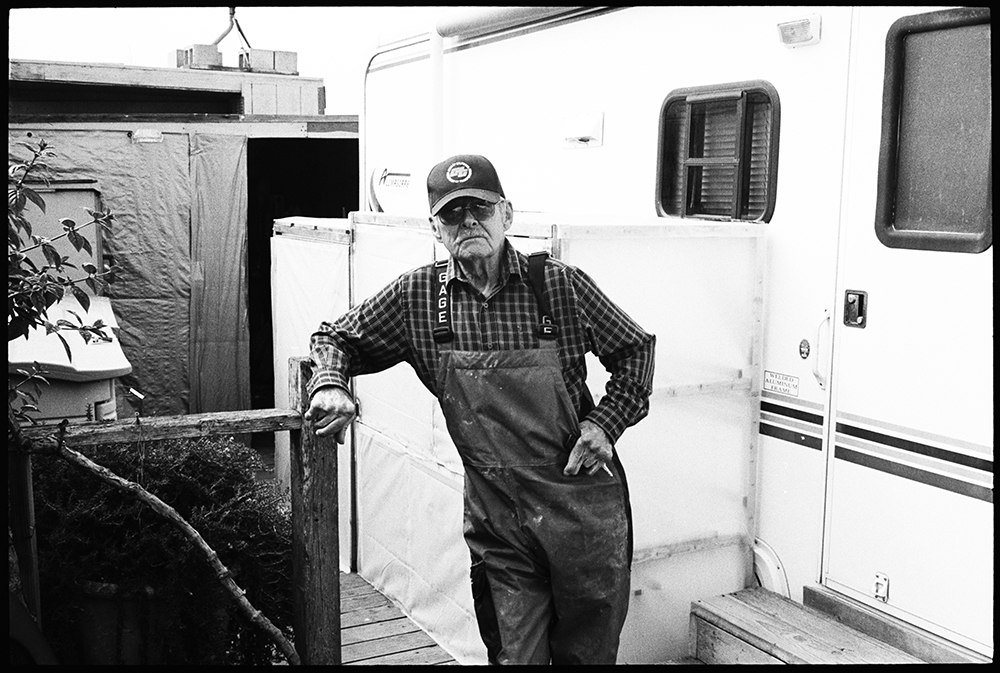

After nearly five decades, the long-term travel trailers at Lawson’s Landing in Dillon Beach are approaching the final year of their tenure . . .

Lawson’s tenants sad as they enter final year

After nearly five decades, the long-term travel trailers at Lawson’s Landing in Dillon Beach are approaching the final year of their tenure . . .