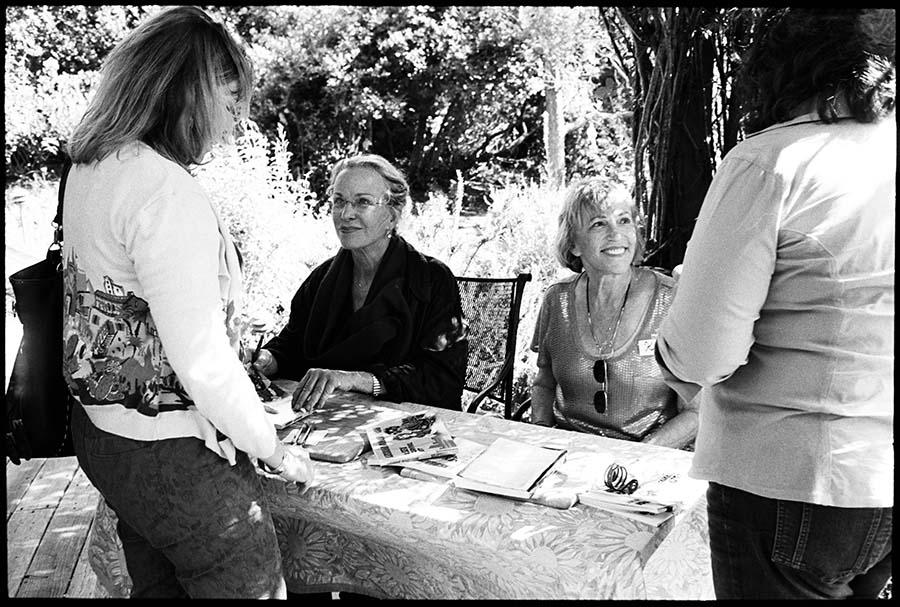

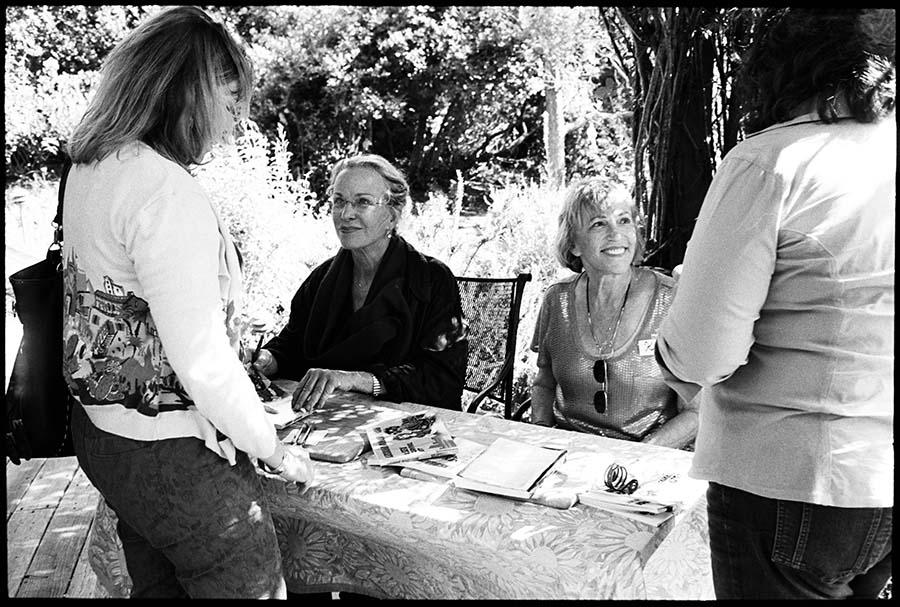

Kim Chernin, a prolific author who explored the modern woman’s search for self-identity, died on Dec. 17 of Covid-19. She was . . .

Kim Chernin, who lived to write, dies at 80

Kim Chernin, a prolific author who explored the modern woman’s search for self-identity, died on Dec. 17 of Covid-19. She was . . .