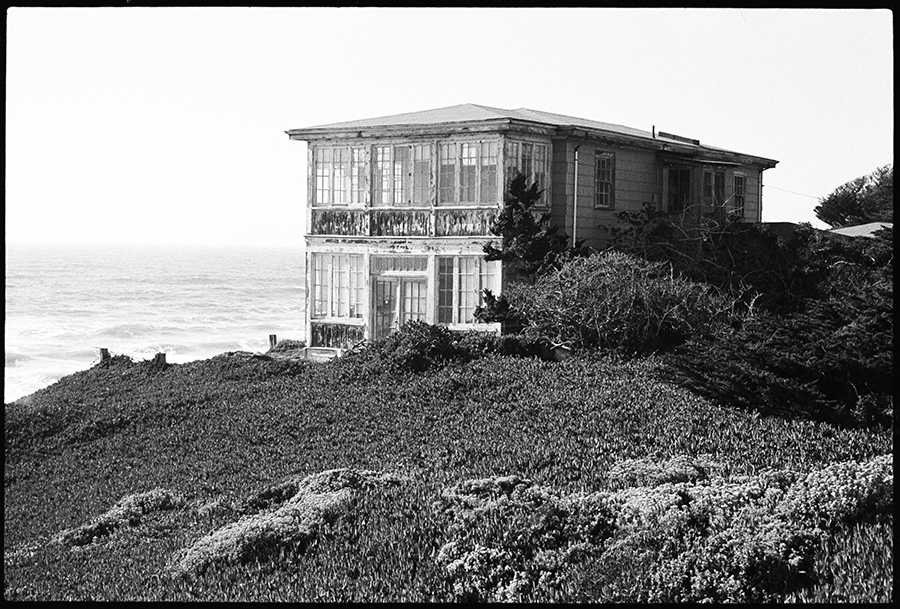

The Point Reyes National Seashore is on the cusp of taking possession of a historic residence sitting on sandstone cliffs overlooking South Beach, between B . . .

Historic bluffside home to become park property

The Point Reyes National Seashore is on the cusp of taking possession of a historic residence sitting on sandstone cliffs overlooking South Beach, between B . . .