In 1957 a man named Henry Molaison, who became one of psychology’s most famous patients, had his hippocampus removed in an attempt to . . .

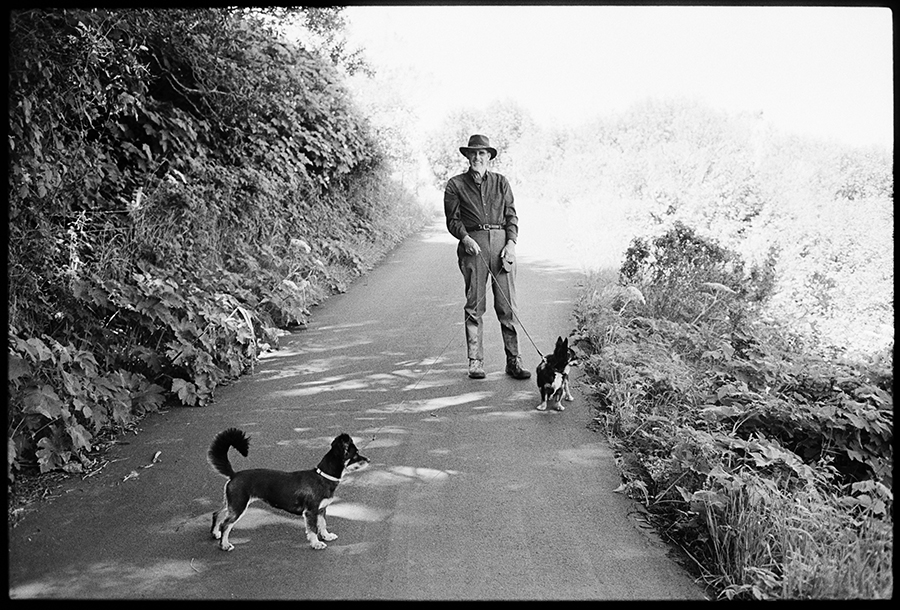

Don MacKay: A pioneer at the intersection of language and memory

In 1957 a man named Henry Molaison, who became one of psychology’s most famous patients, had his hippocampus removed in an attempt to . . .