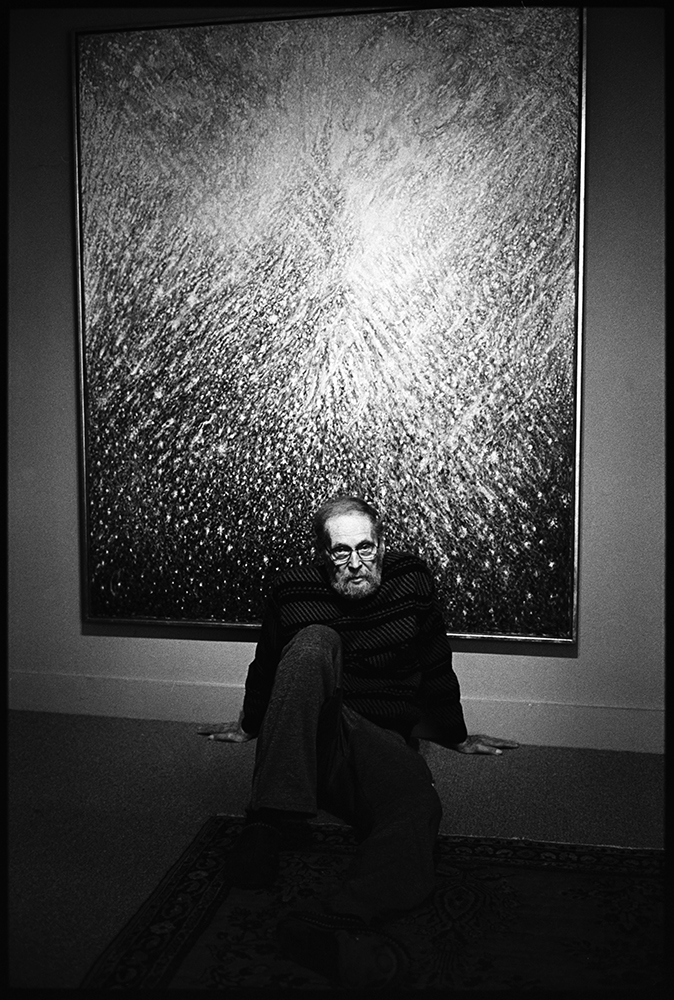

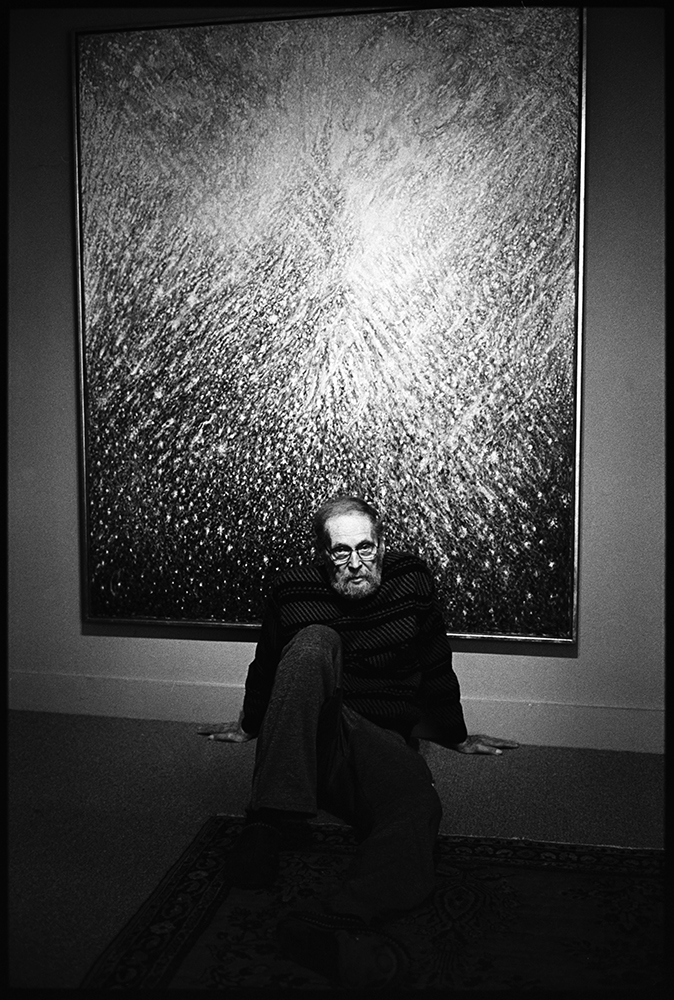

Art Holman, a painter who has lived in San Geronimo Valley for decades, wasn’t sure he would make it to the opening of . . .

Art Holman: Painting the cosmos through the unconscious

Art Holman, a painter who has lived in San Geronimo Valley for decades, wasn’t sure he would make it to the opening of . . .