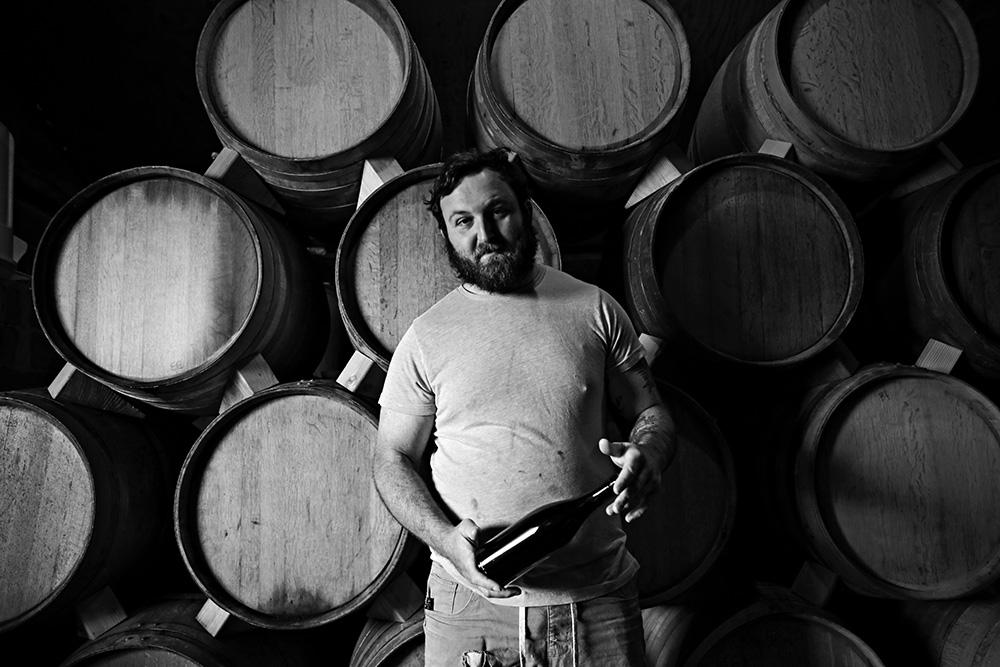

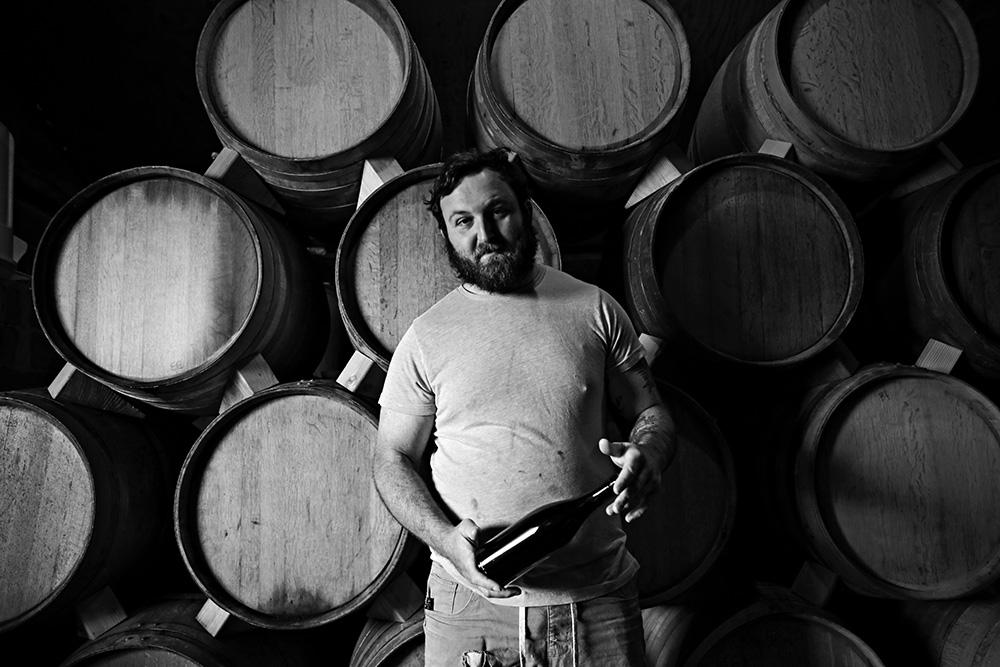

Avi Deixler will readily tell you that he doesn’t know how to make wine. “Pretty much I use intuition and hard work,” said . . .

West Marin’s Absentee Winery: All about natural chemistry

Avi Deixler will readily tell you that he doesn’t know how to make wine. “Pretty much I use intuition and hard work,” said . . .