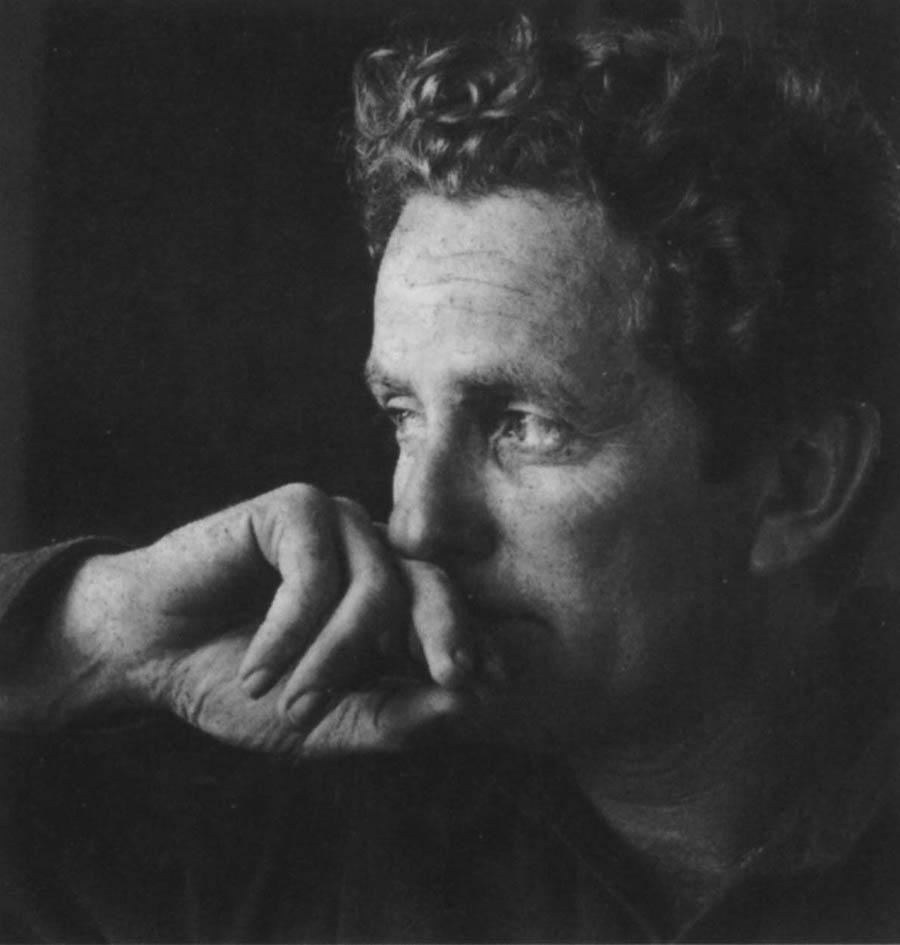

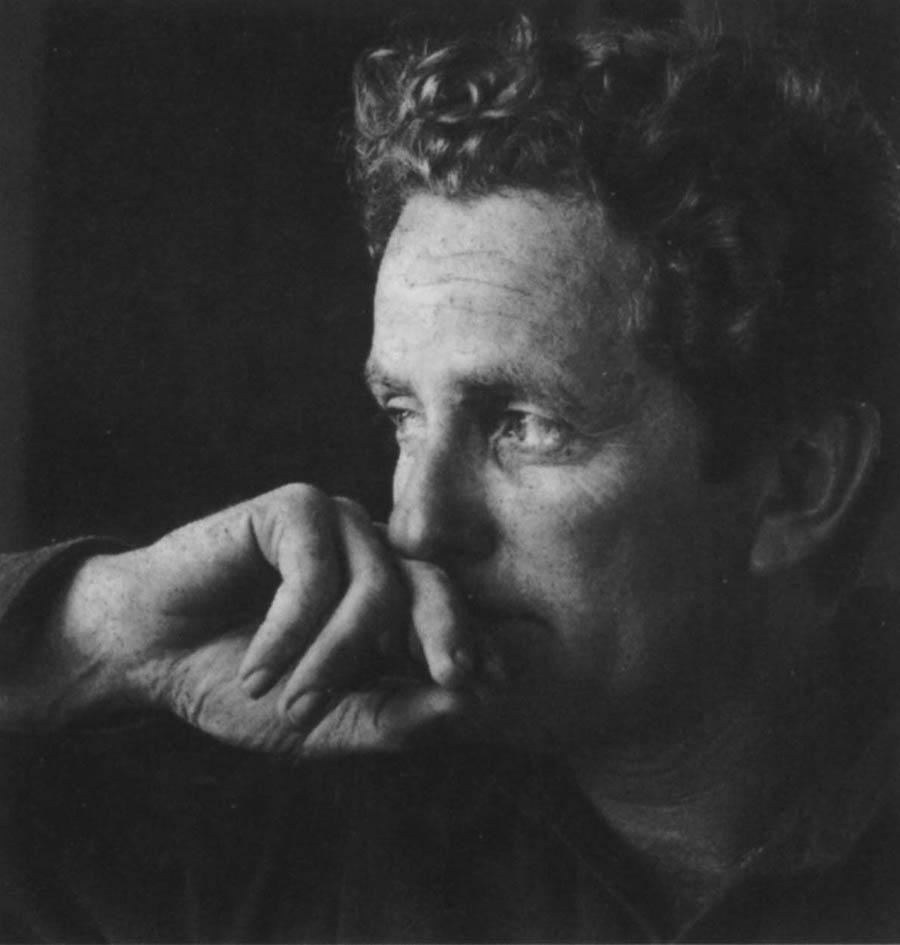

Paul Harris, an artist, sculptor and art professor who lived in Bolinas for 55 years, died on May 13 in Bozeman, Mont., at age . . .

Paul Harris, of Bolinas, harnessed power in art

Paul Harris, an artist, sculptor and art professor who lived in Bolinas for 55 years, died on May 13 in Bozeman, Mont., at age . . .