So much in Nicholas Giacomini’s life is entwined with Toby’s Feed Barn. As the grandson of its founder, he got his first . . .

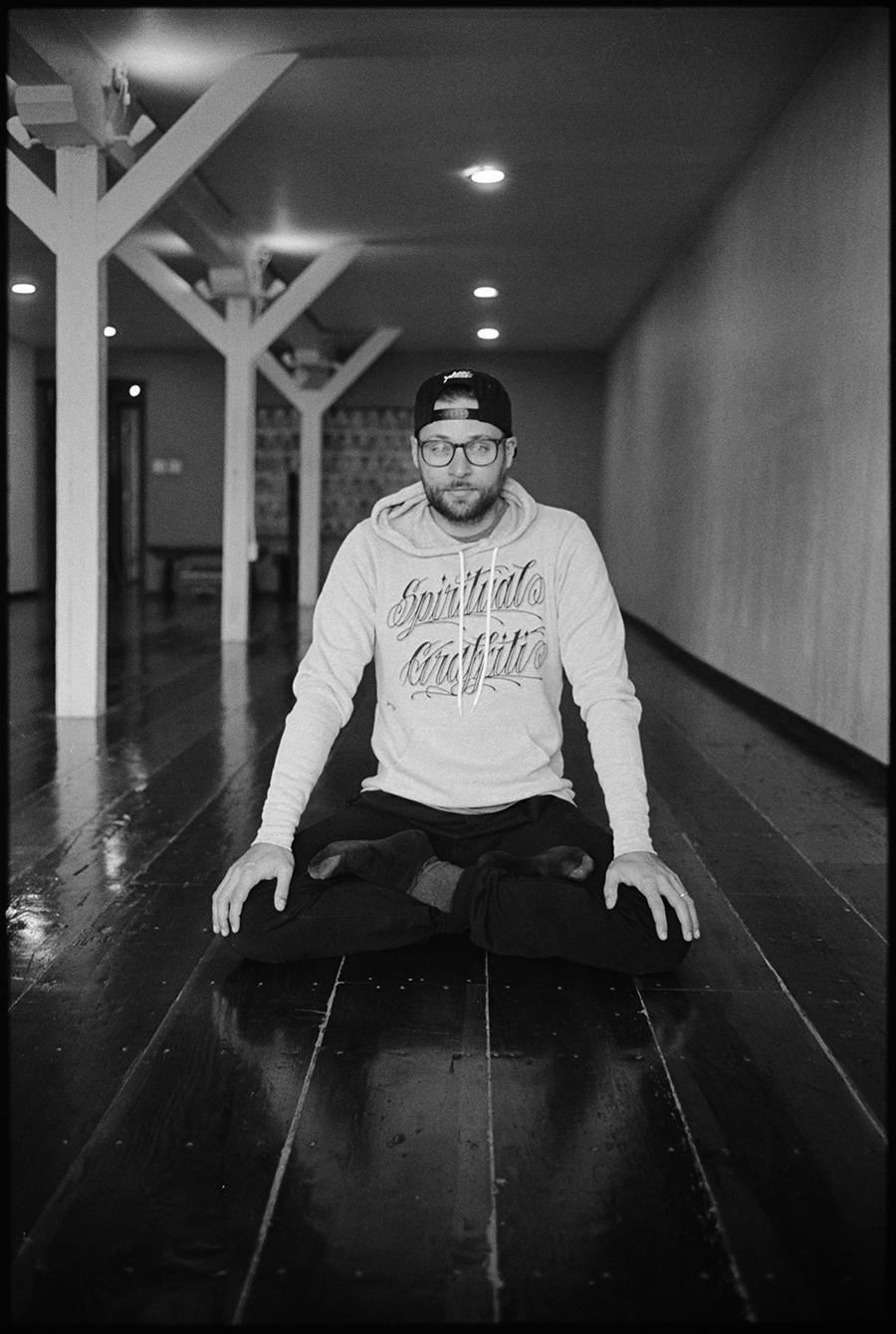

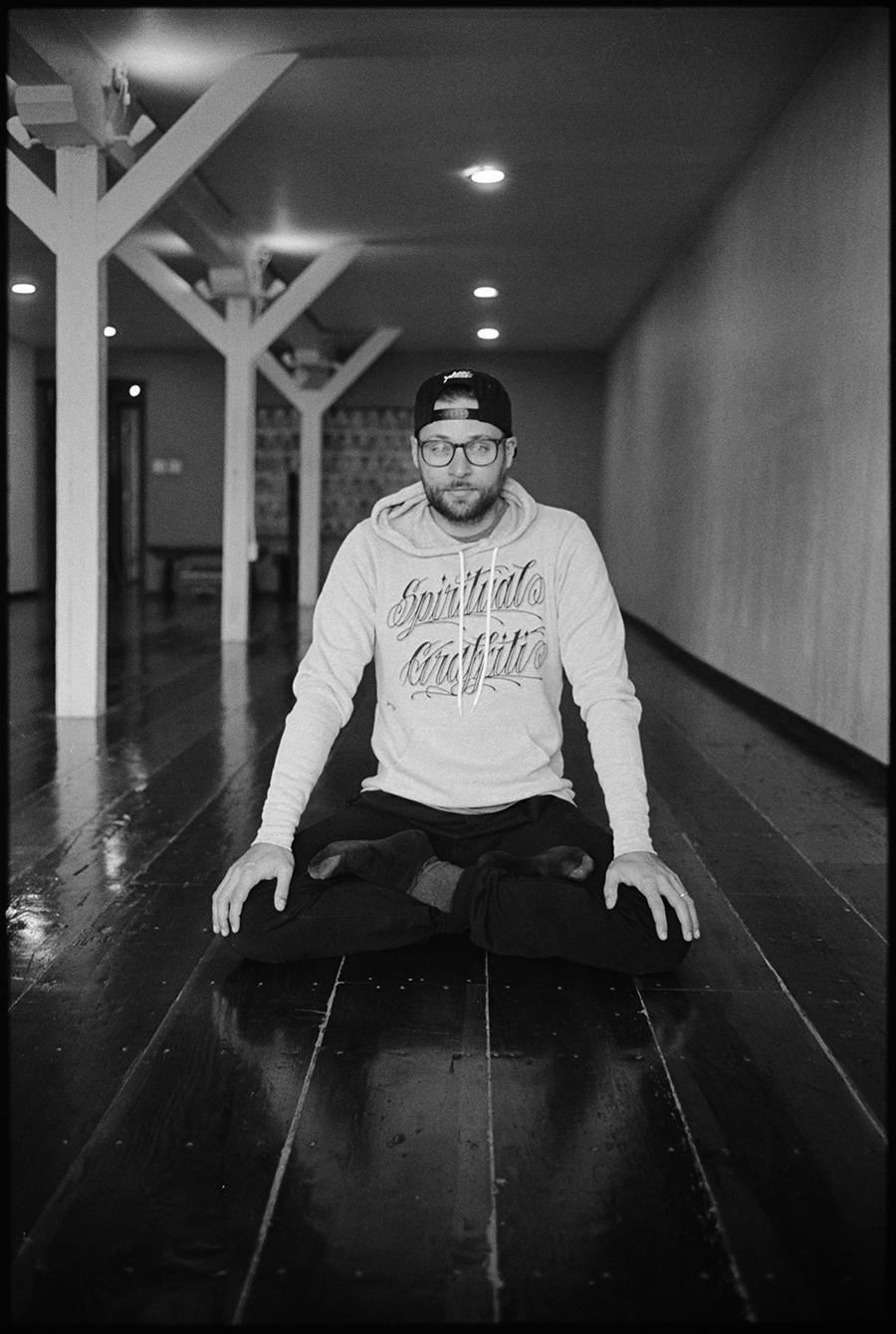

MC Yogi on finding his true path

So much in Nicholas Giacomini’s life is entwined with Toby’s Feed Barn. As the grandson of its founder, he got his first . . .