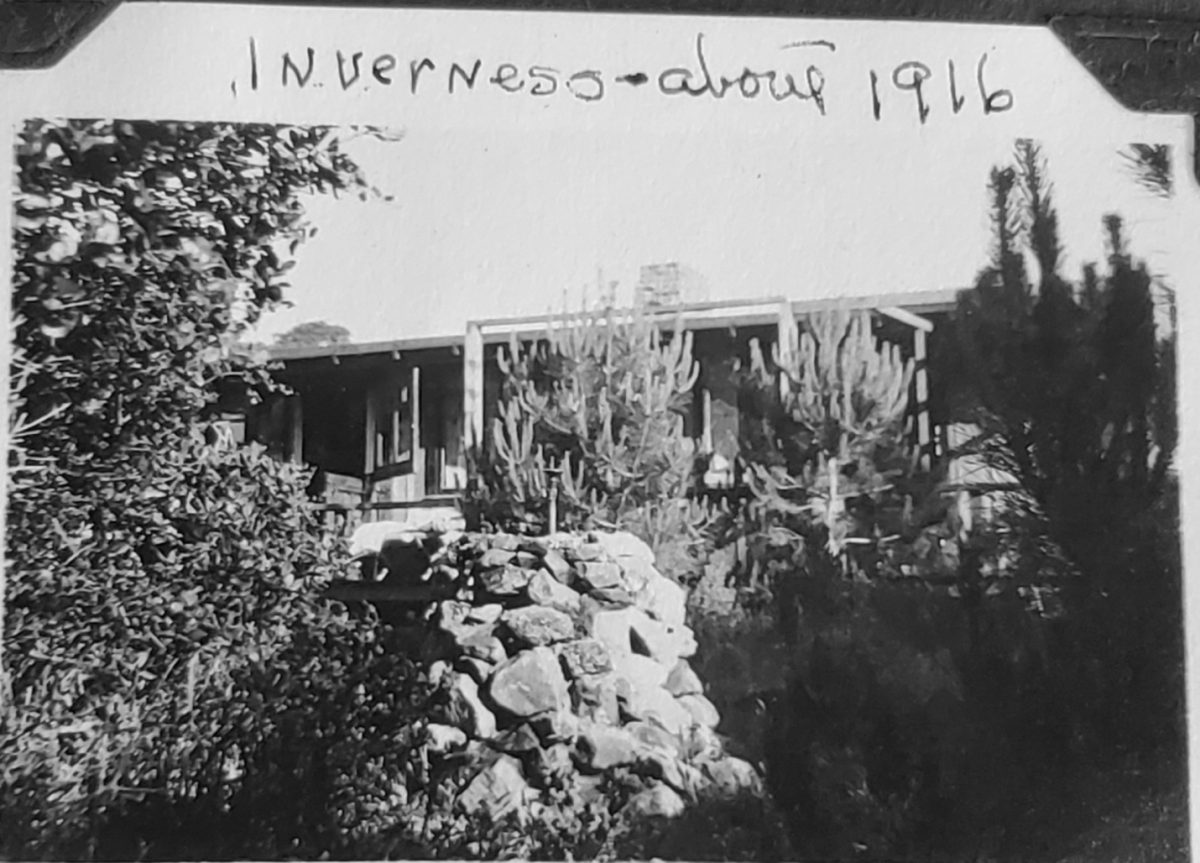

In the early decades of the 20th century, Inverness was the summer destination of several families, especially Berkeley families, for whom architect Julia Morgan undertook . . .

Inverness by design: Julia Morgan

In the early decades of the 20th century, Inverness was the summer destination of several families, especially Berkeley families, for whom architect Julia Morgan undertook . . .