While waiting for a coffee at the kiosk outside the Coast Café, veteran birder and illustrator Keith Hansen heard a chirp and glanced up . . .

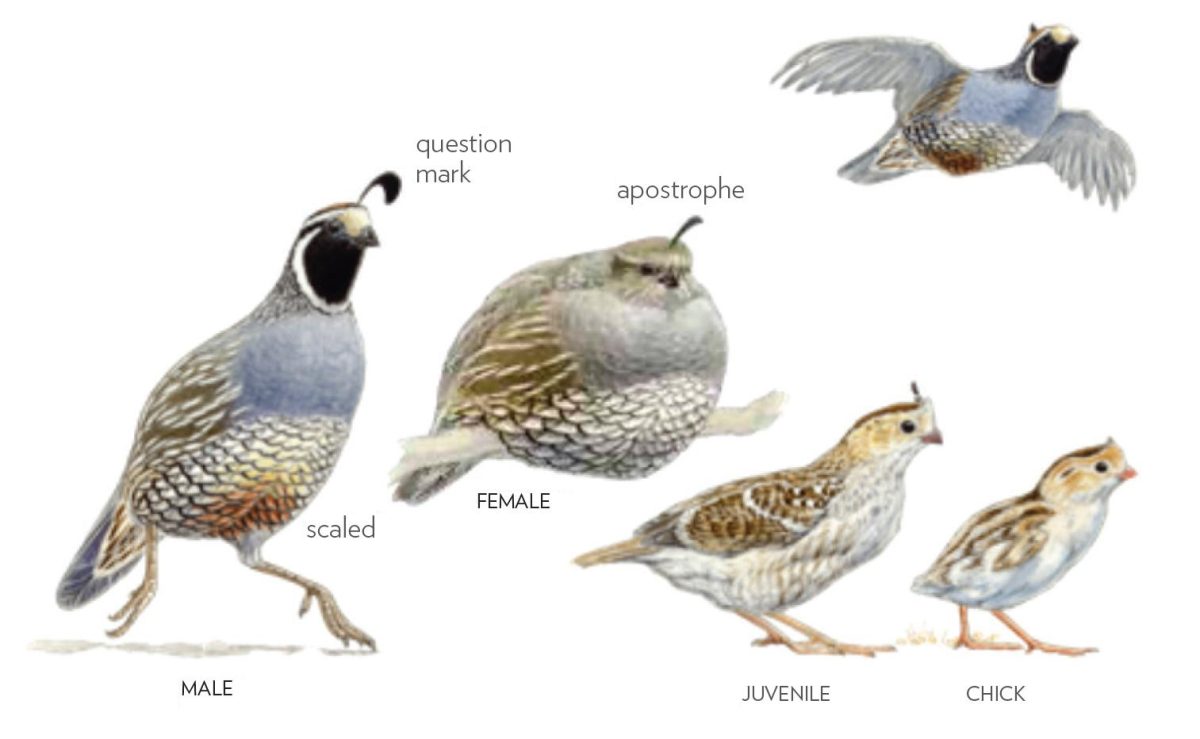

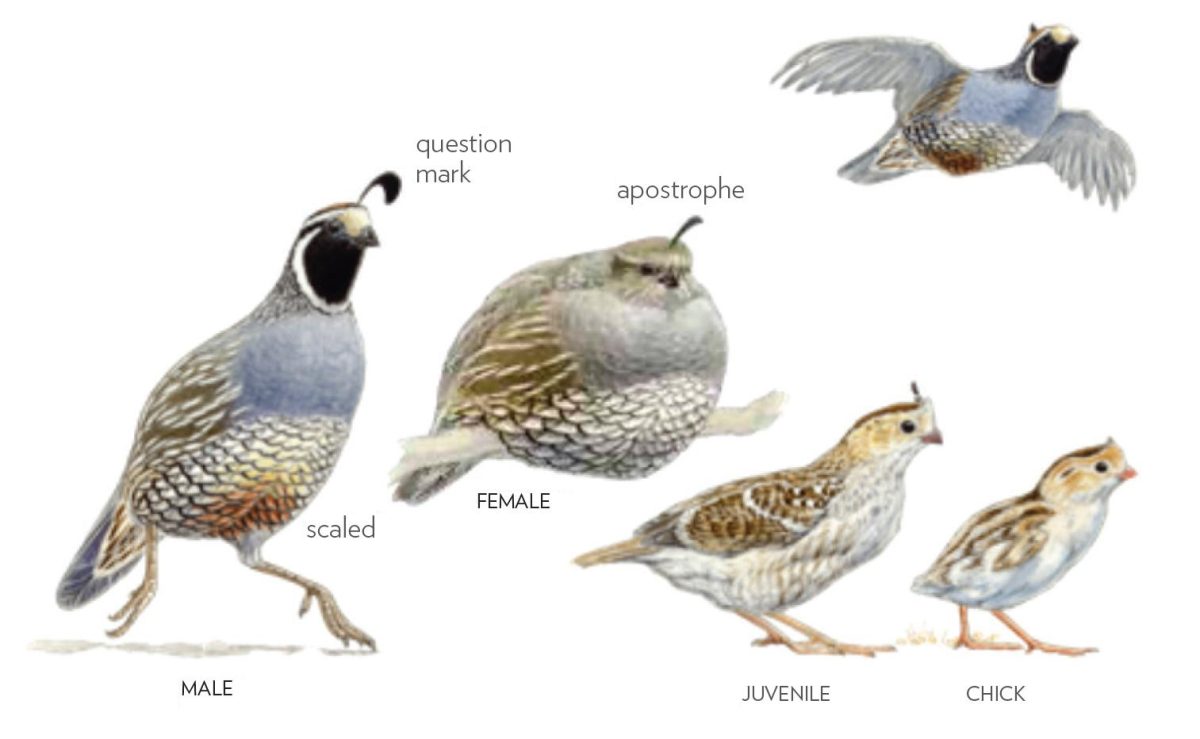

Bolinas artist captures Sierra birds in new guide

While waiting for a coffee at the kiosk outside the Coast Café, veteran birder and illustrator Keith Hansen heard a chirp and glanced up . . .