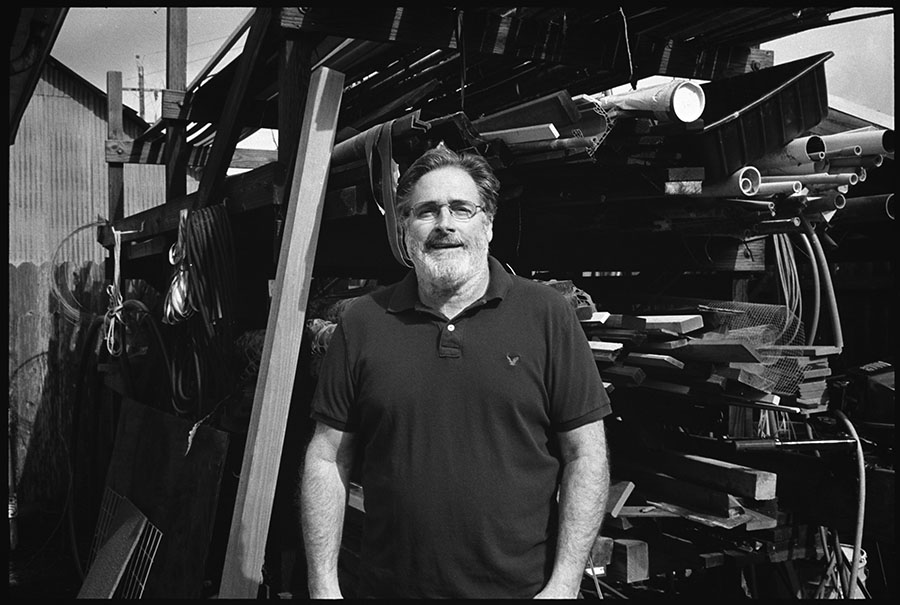

Dennis Rodoni has deep roots in West Marin. His maternal grandparents, the Blooms, ranched in Olema. His paternal grandparents moved to Point Reyes . . .

West Marin, meet Dennis Rodoni

Dennis Rodoni has deep roots in West Marin. His maternal grandparents, the Blooms, ranched in Olema. His paternal grandparents moved to Point Reyes . . .