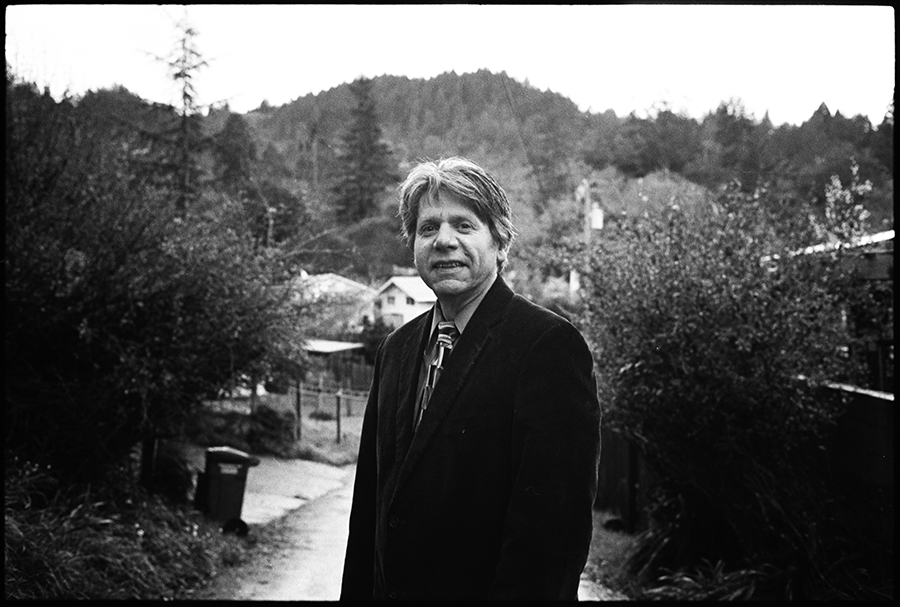

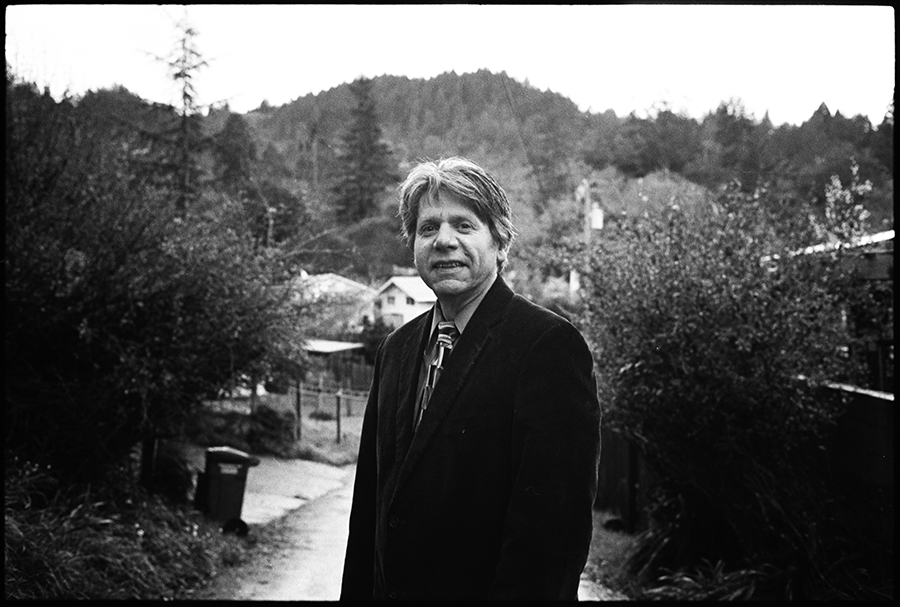

Brian Staley said his mother, an active campaigner for politicians when he was growing up in San Anselmo, had a “deep reverence for . . .

West Marin, meet Brian Staley

Brian Staley said his mother, an active campaigner for politicians when he was growing up in San Anselmo, had a “deep reverence for . . .