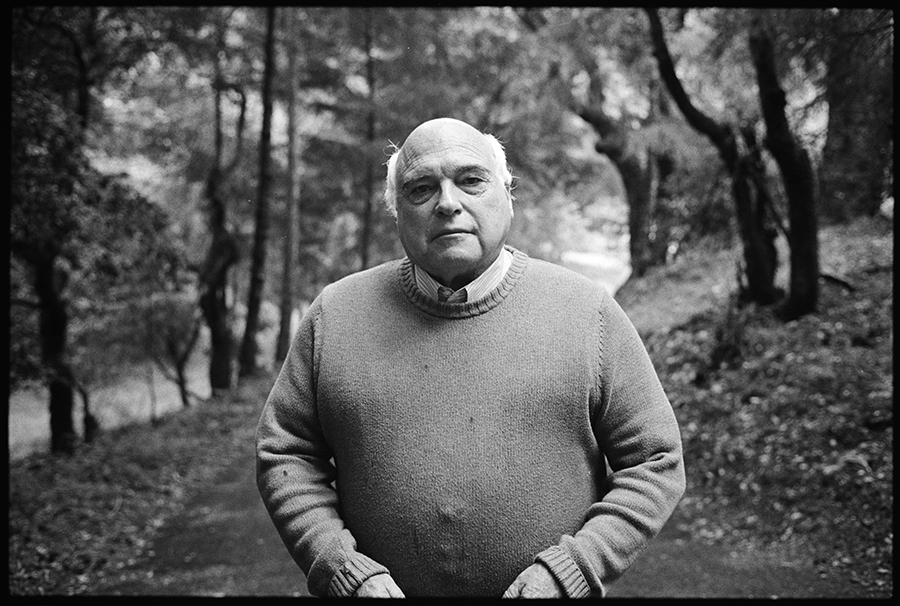

Alex Easton-Brown says exactly what he thinks, which can make him sound off-the-wall or curiously insightful, depending on the topic . . .

West Marin, meet Alex Easton-Brown

Alex Easton-Brown says exactly what he thinks, which can make him sound off-the-wall or curiously insightful, depending on the topic . . .