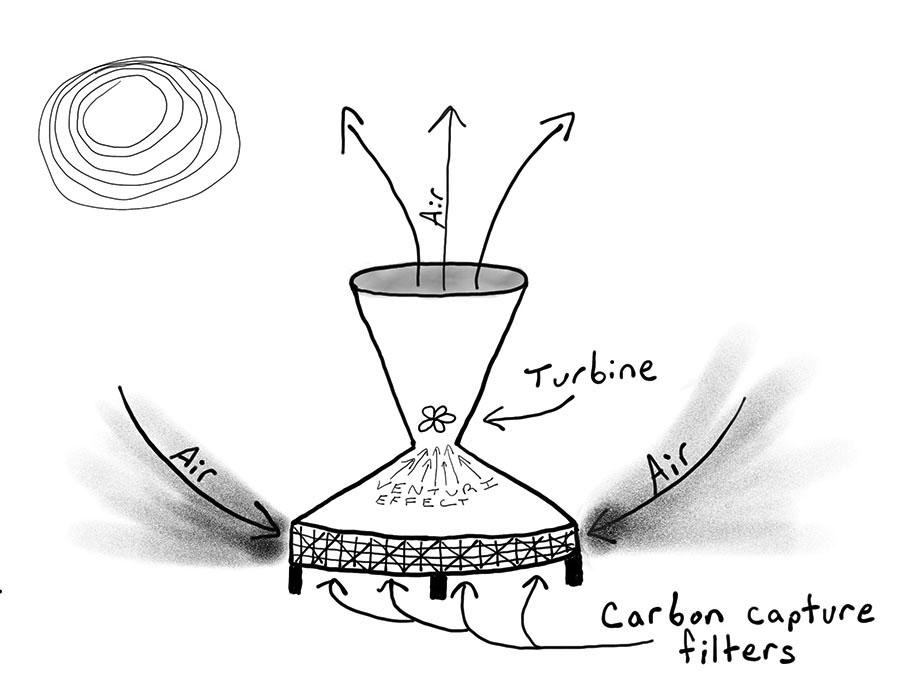

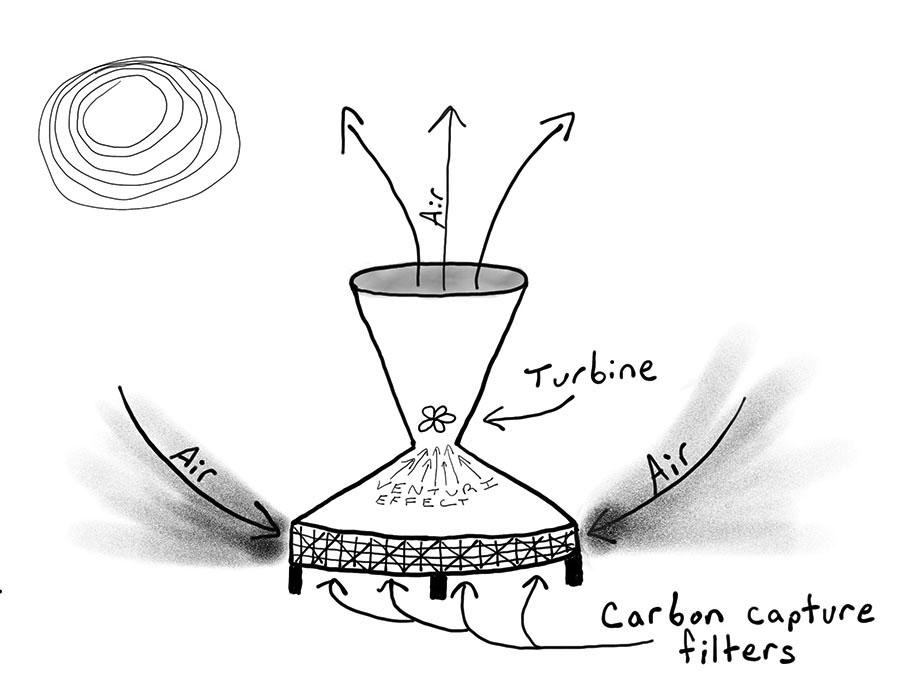

A mason in San Geronimo has developed a prototype for a giant chimney that moves massive amounts of air using heat from the sun . . .

Solar air chimney: One man’s device to help reverse disaster

A mason in San Geronimo has developed a prototype for a giant chimney that moves massive amounts of air using heat from the sun . . .