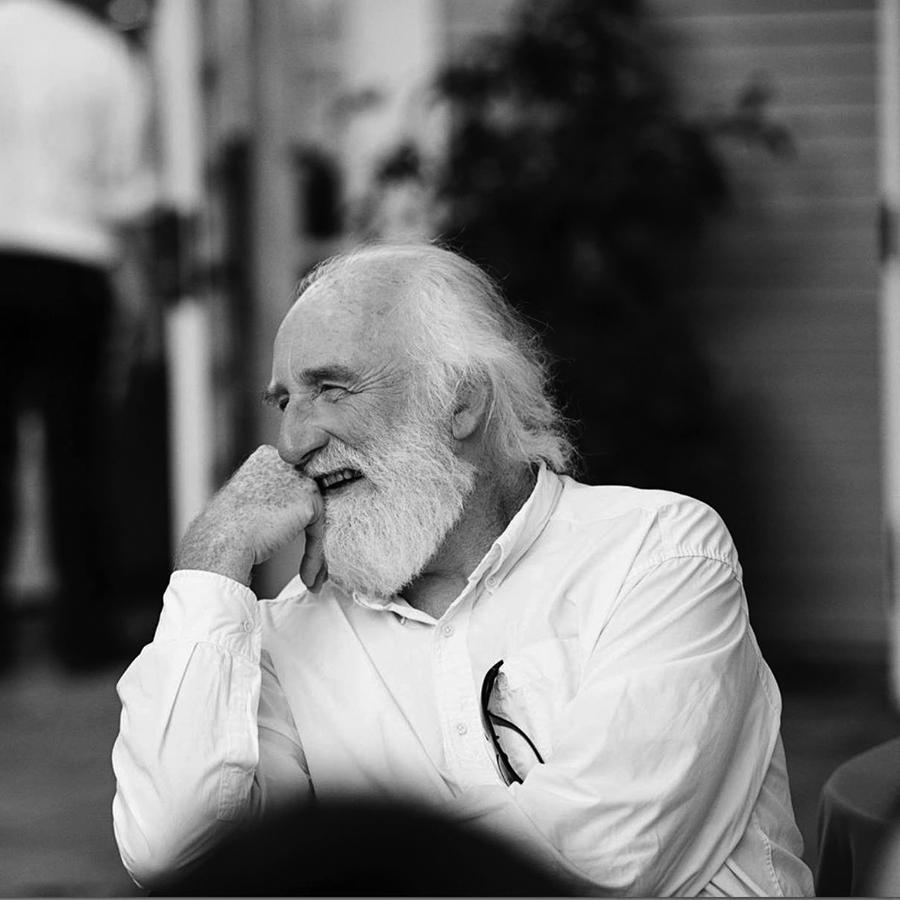

Paul Reffell, a Marshall mainstay who sailed around the world, penned two books, sparked multiple protest movements, and loved fiercely, died on Jan. 3 . . .

Paul Reffell, actor and adventurer, dies at 68

Paul Reffell, a Marshall mainstay who sailed around the world, penned two books, sparked multiple protest movements, and loved fiercely, died on Jan. 3 . . .