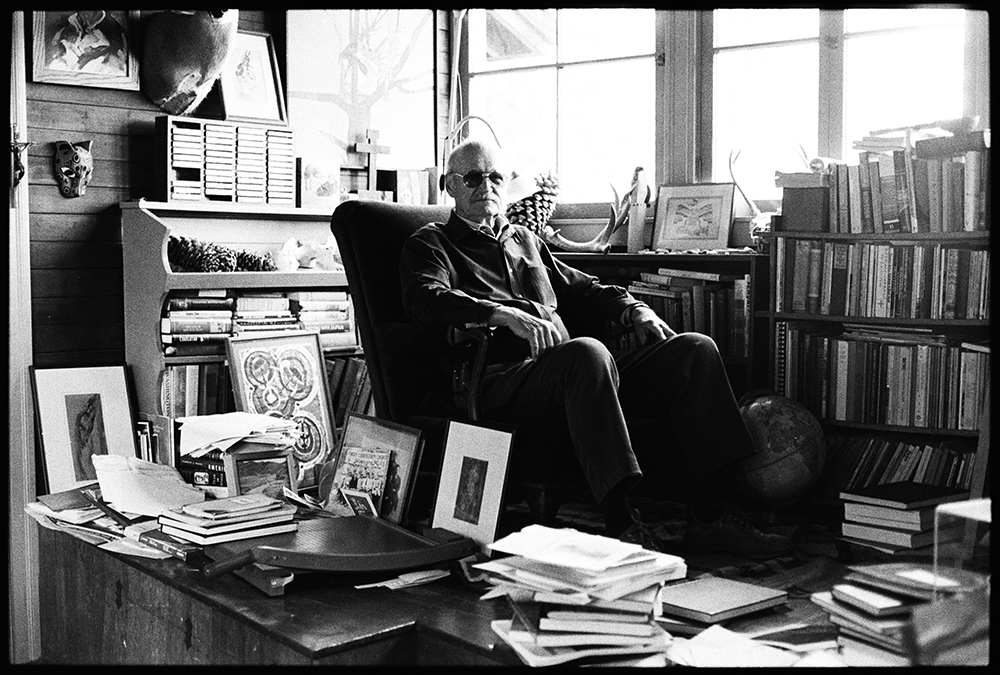

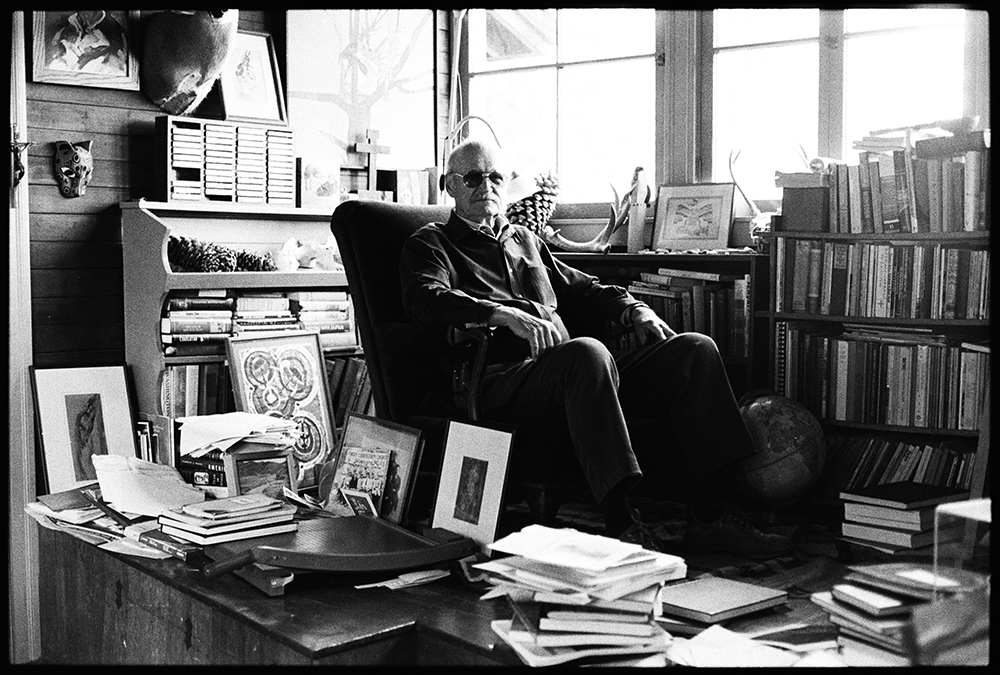

Dr. Michael Whitt, a Texas native who forsook a career in petroleum engineering to study medicine, served countless families during his four decades . . .

Michael Whitt: A life in country medicine

Dr. Michael Whitt, a Texas native who forsook a career in petroleum engineering to study medicine, served countless families during his four decades . . .