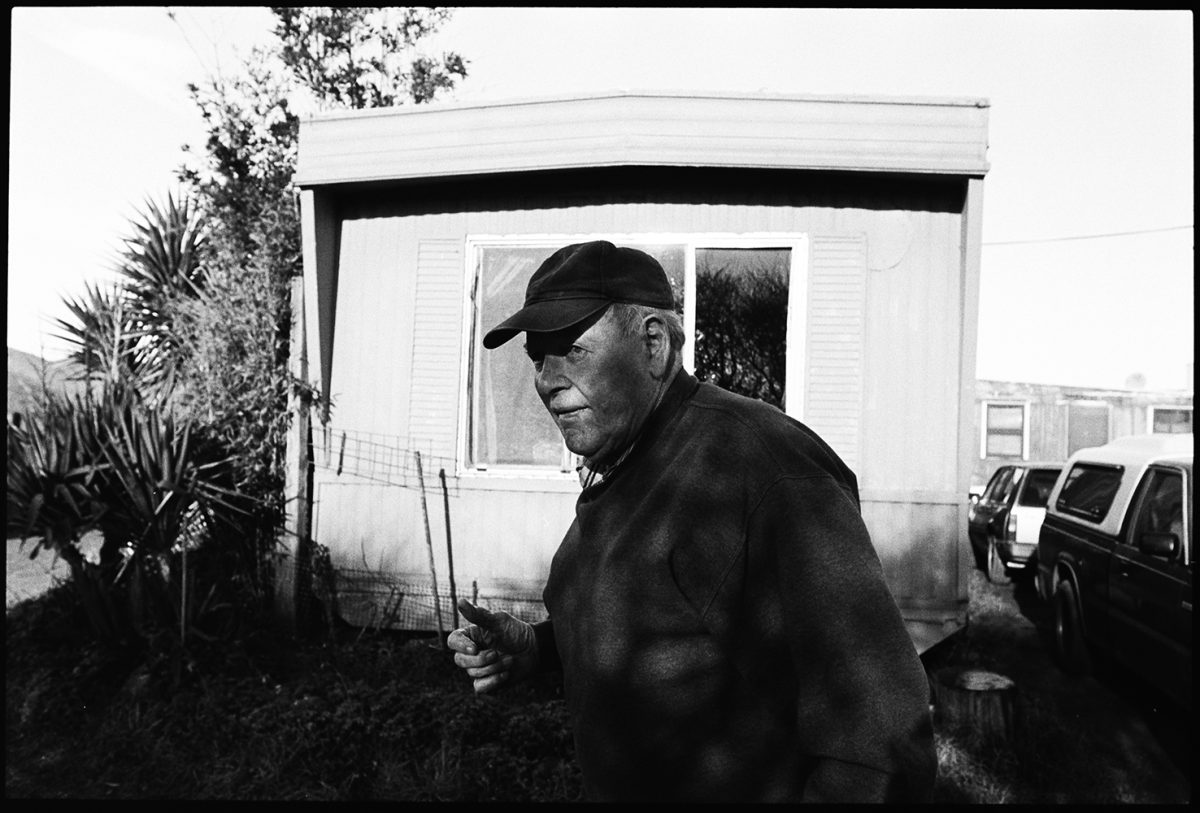

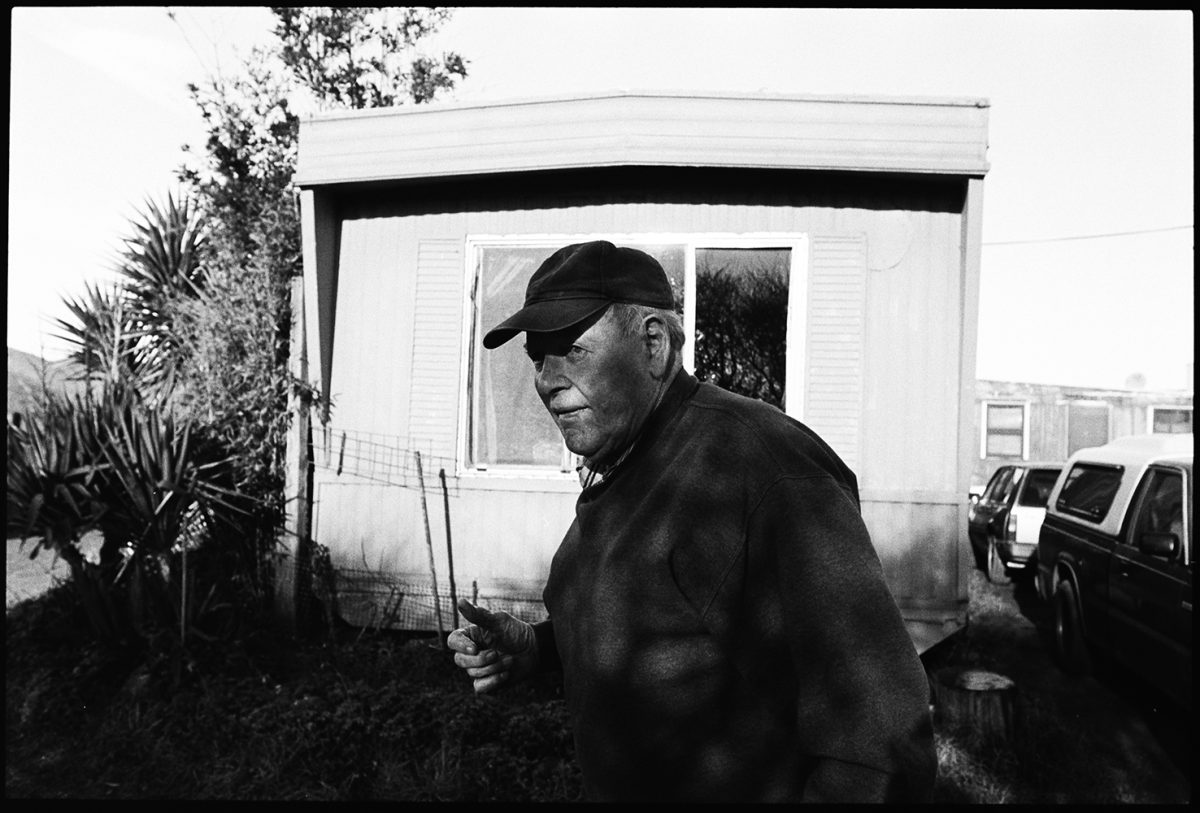

Two years after a 25-year reservation of use and occupancy for Leroy Martinelli’s ranch on Tomales Bay expired, several families are preparing . . .

Martinelli to relinquish Tomales Bay cattle ranch

Two years after a 25-year reservation of use and occupancy for Leroy Martinelli’s ranch on Tomales Bay expired, several families are preparing . . .