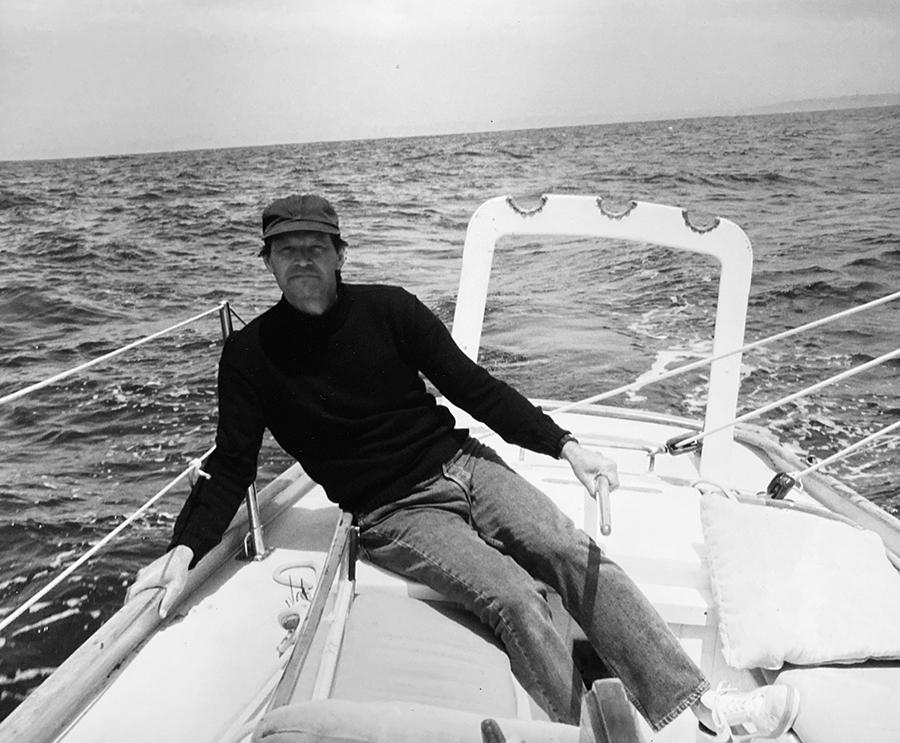

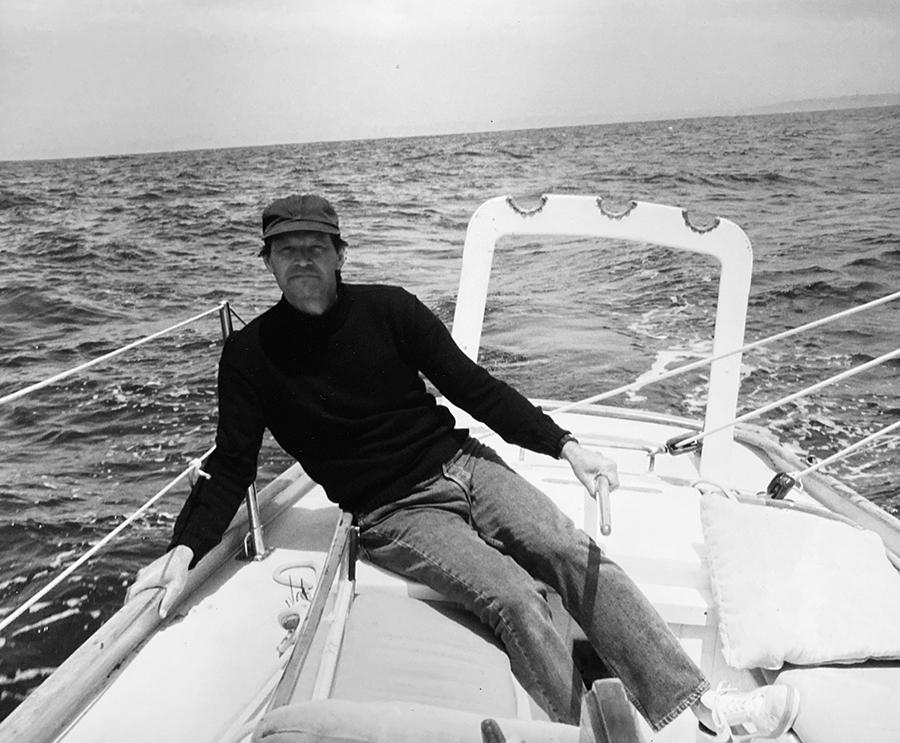

Mark Ropers, an attorney, a sailor and a watercolorist known for his dry humor and gentle demeanor, died at home in Inverness on April . . .

Mark Ropers, who lived gently on the bay

Mark Ropers, an attorney, a sailor and a watercolorist known for his dry humor and gentle demeanor, died at home in Inverness on April . . .