In response to fears that West Marin’s agricultural lands would succumb to development, destroying an economy and a tradition of stewardship more than a . . .

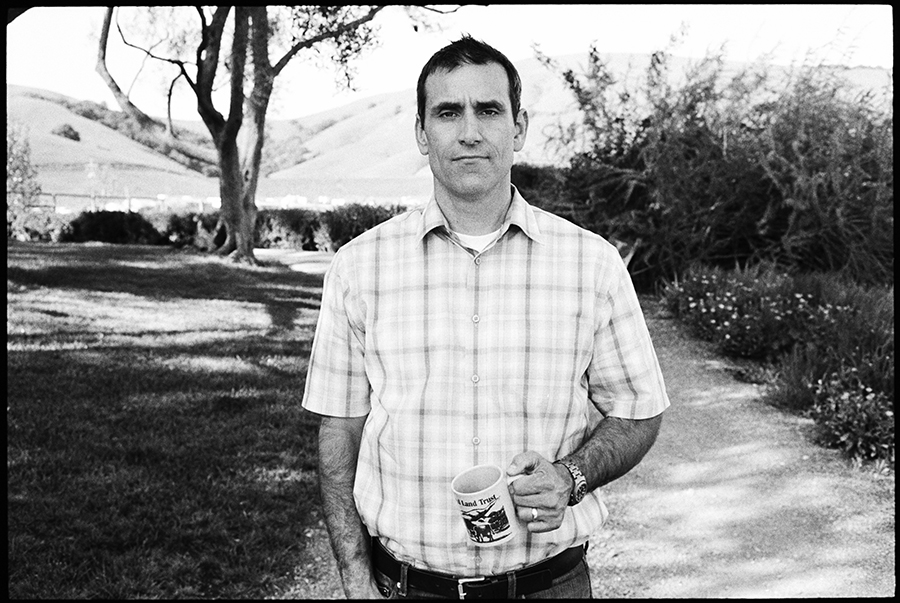

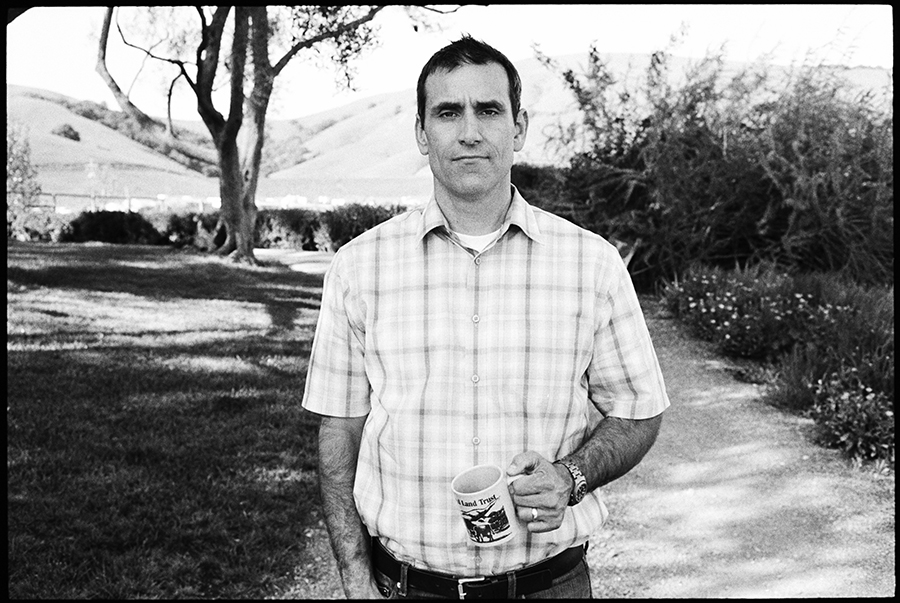

Jamison Watts on the future of farmland conservation in Marin

In response to fears that West Marin’s agricultural lands would succumb to development, destroying an economy and a tradition of stewardship more than a . . .