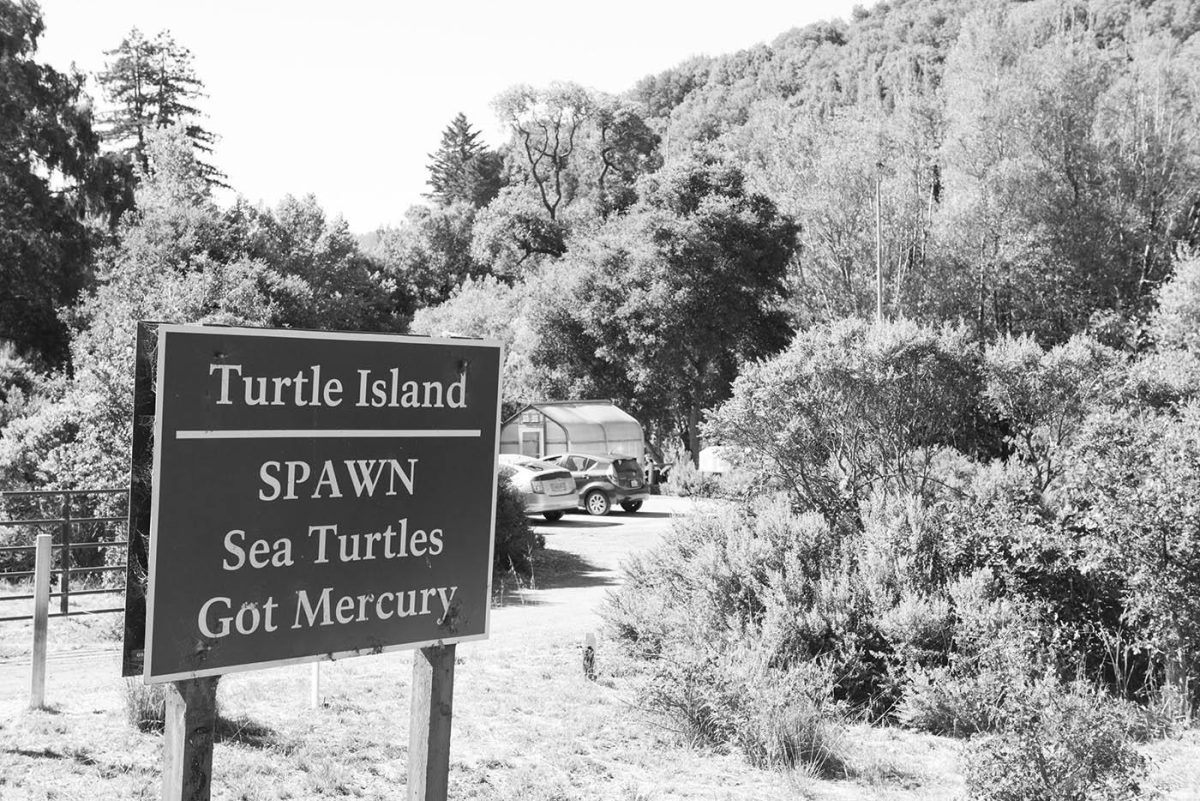

In 2017, Callie Veelenturf won the first conservation scholarship given out by Turtle Island Restoration Network, which meant she’d be traveling with Todd . . .

Former TIRN staff allege harassment

In 2017, Callie Veelenturf won the first conservation scholarship given out by Turtle Island Restoration Network, which meant she’d be traveling with Todd . . .