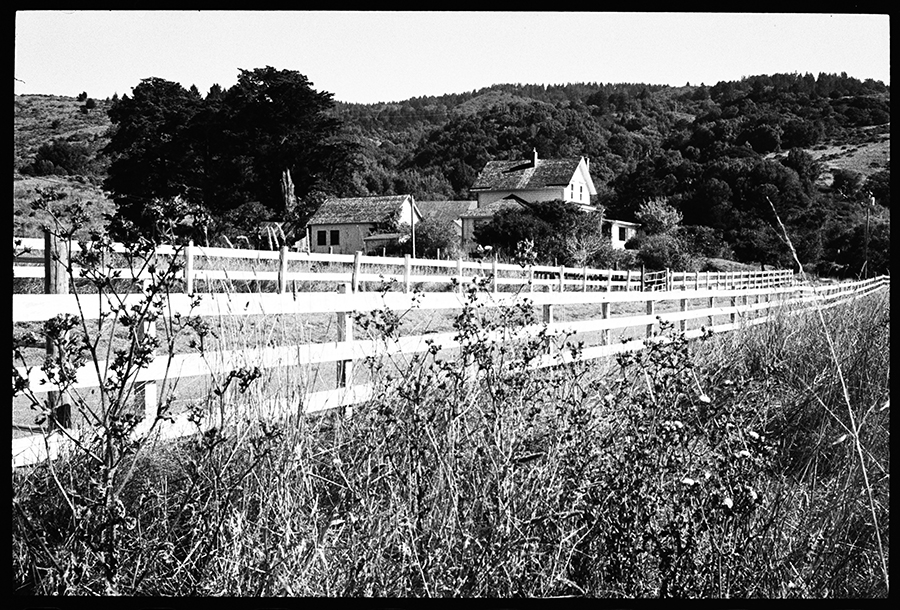

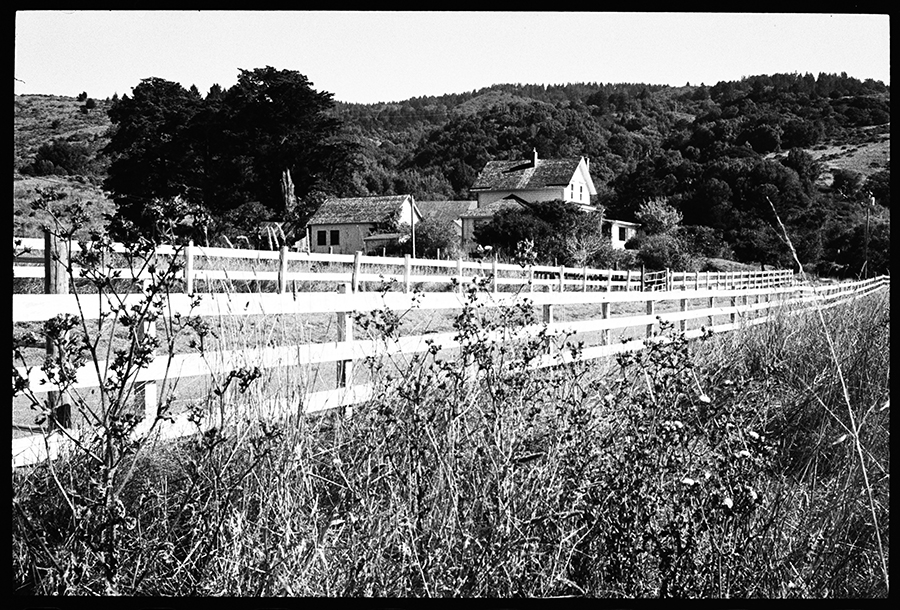

Two individuals who were evicted from ranches in the Point Reyes National Seashore in the last 15 years have asked the National Park Service . . .

Former ranch lands at center of new pleas

Two individuals who were evicted from ranches in the Point Reyes National Seashore in the last 15 years have asked the National Park Service . . .