One day, a man in Marin got a phone call that he had won $5 million in a sweepstakes contest. He could get all . . .

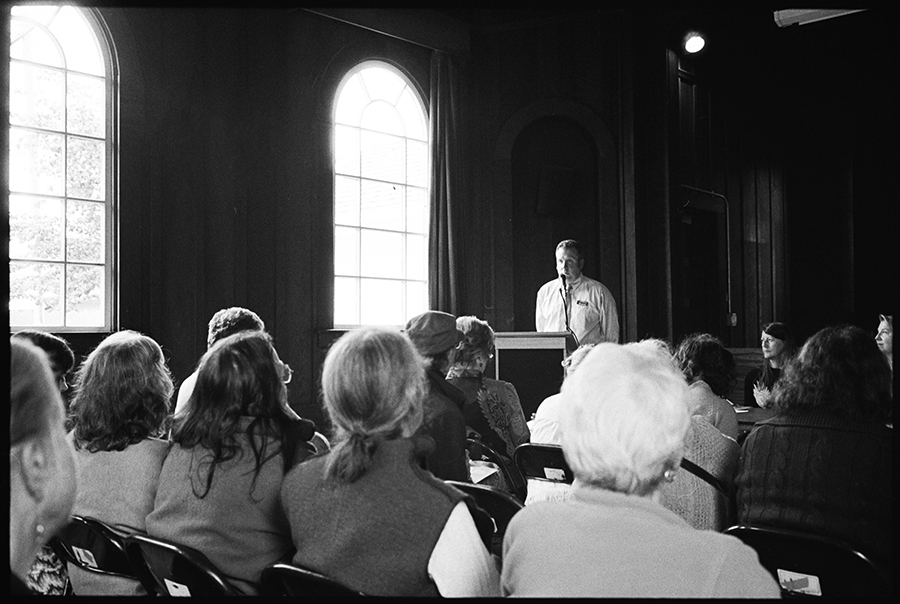

Experts advise elders on avoiding financial fraud

One day, a man in Marin got a phone call that he had won $5 million in a sweepstakes contest. He could get all . . .