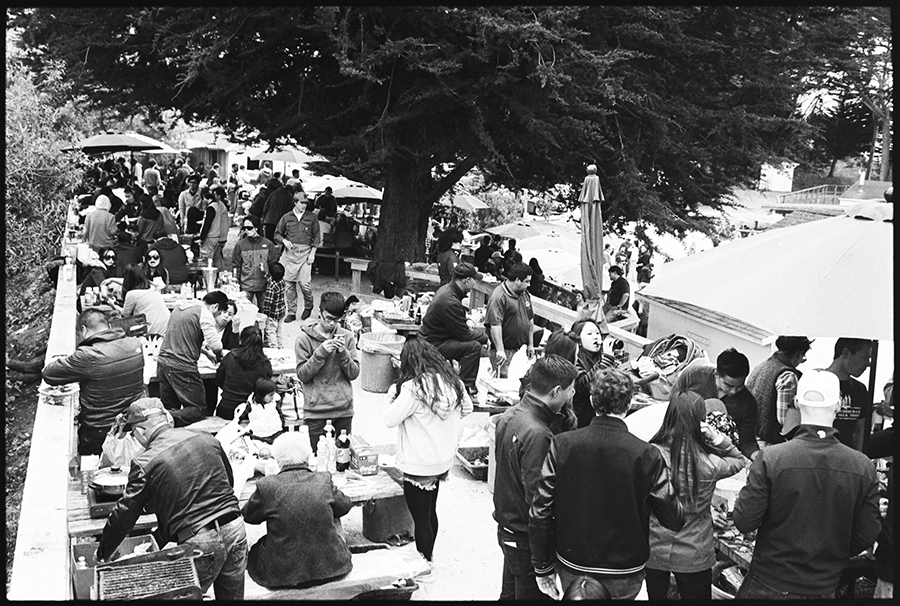

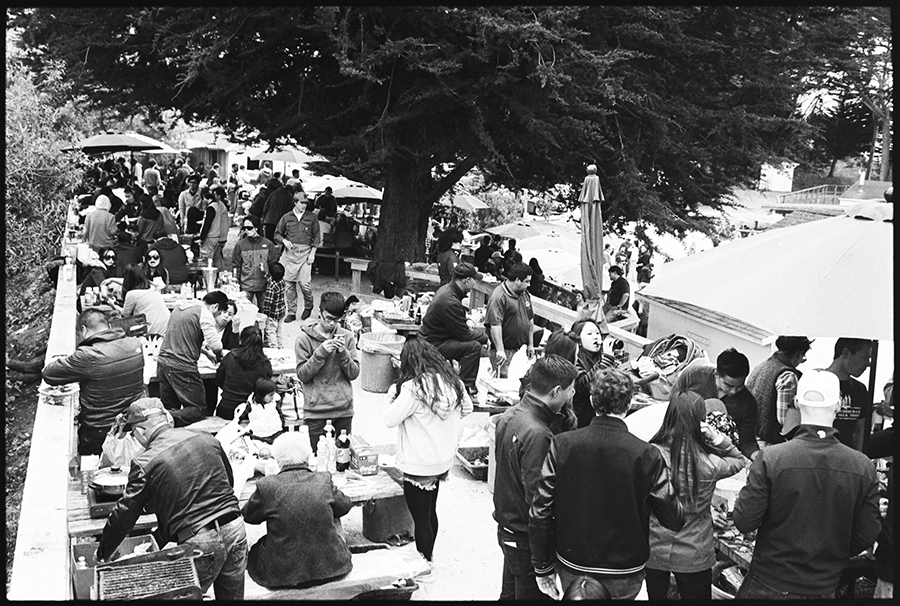

Tomales Bay Oyster Company has been ordered to limit sales and remove its popular picnic and barbeque sites by the end of the month . . .

Everyday retail and picnics nixed at TBOC

Tomales Bay Oyster Company has been ordered to limit sales and remove its popular picnic and barbeque sites by the end of the month . . .