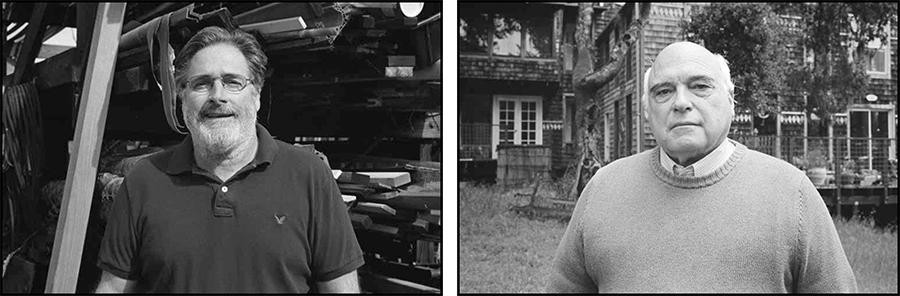

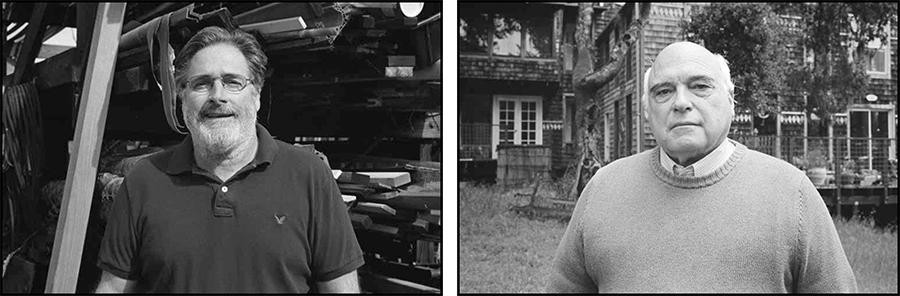

A Lagunitas resident is challenging Supervisor Dennis Rodoni to represent Marin County’s fourth district. Alex Easton-Brown received 5 percent of the vote . . .

Easton-Brown challenges Rodoni in March supervisor race

A Lagunitas resident is challenging Supervisor Dennis Rodoni to represent Marin County’s fourth district. Alex Easton-Brown received 5 percent of the vote . . .