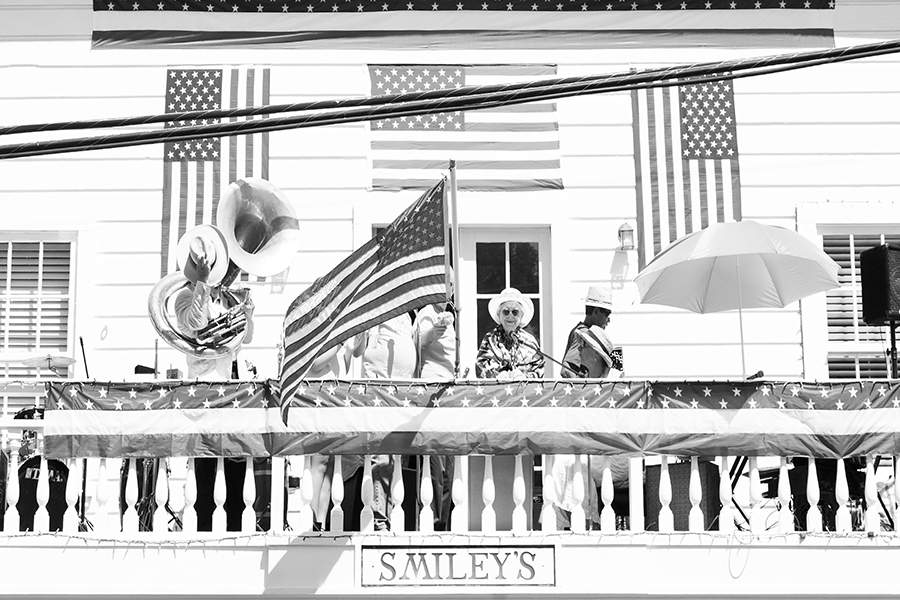

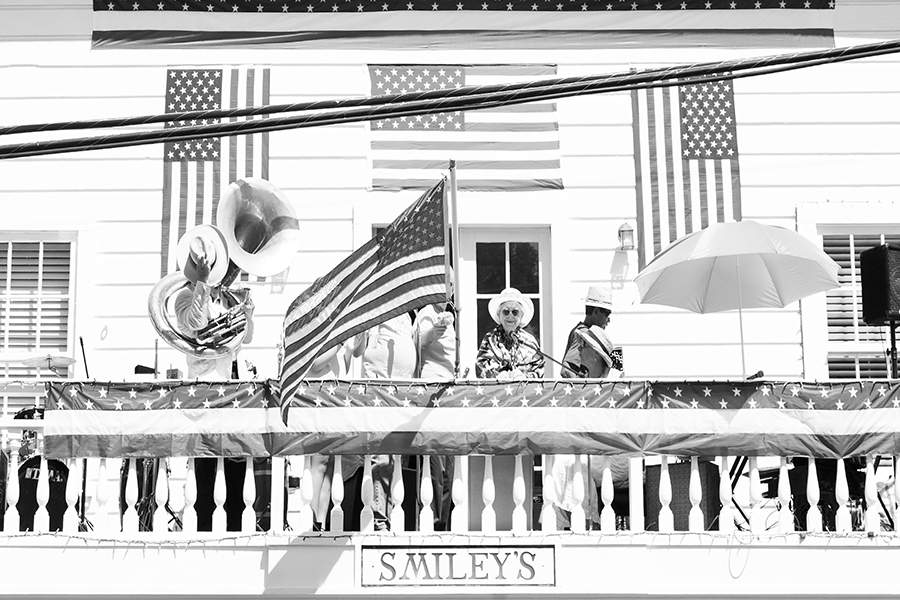

Annie Crotts, who lived in Bolinas since 1925 and belted the Star-Spangled Banner to commence the local Fourth of July parade for more . . .

Annie Crotts, who sang the national anthem for Bolinas, dies at 91

Annie Crotts, who lived in Bolinas since 1925 and belted the Star-Spangled Banner to commence the local Fourth of July parade for more . . .