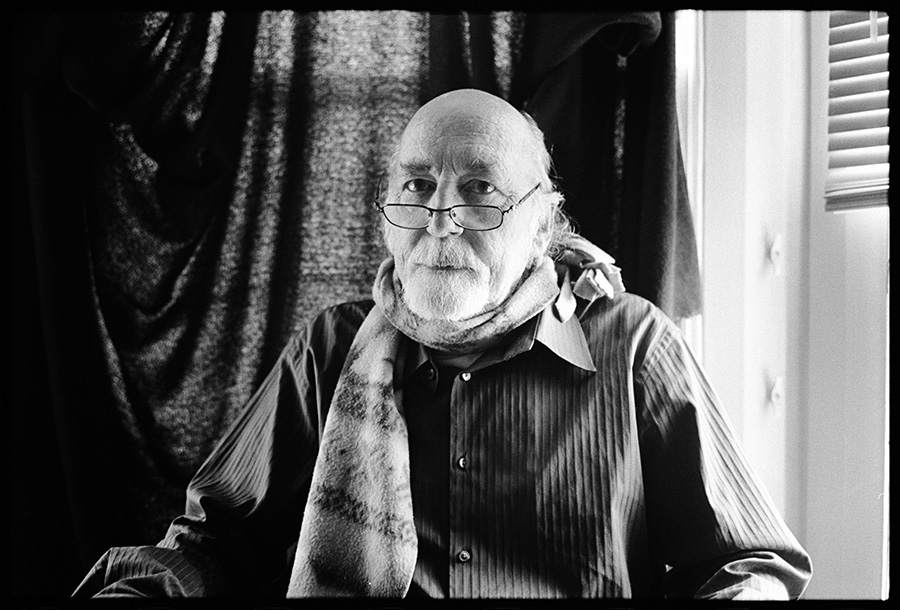

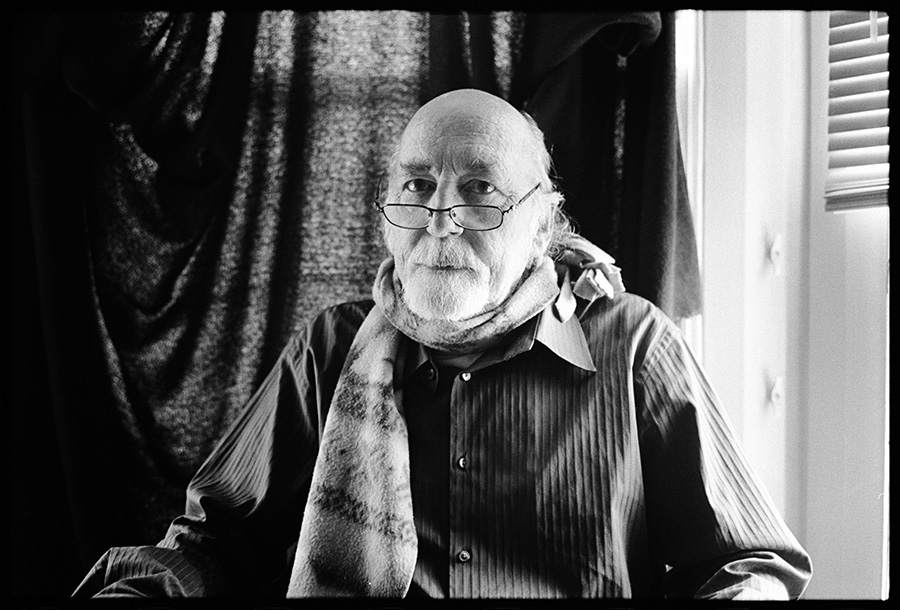

William Radcliffe Baker is a poet and playwright who lives in San Francisco. I met him soon after I arrived in the Bay . . .

W.R. Baker: The outsider

William Radcliffe Baker is a poet and playwright who lives in San Francisco. I met him soon after I arrived in the Bay . . .