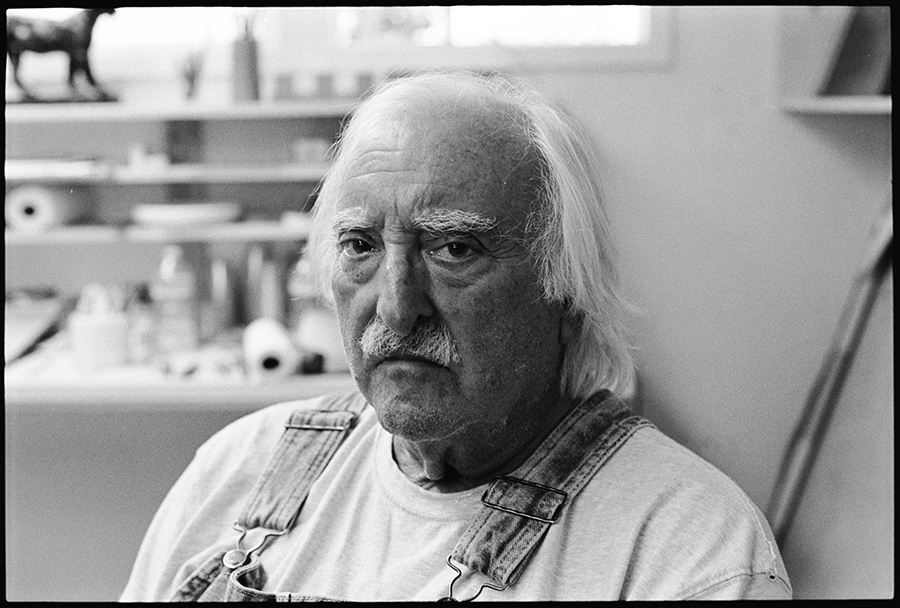

When I met him for this interview, Russell Chatham—painter, printmaker, author, fisherman and restauranteur—gave me a short piece he wrote titled, “Advice . . .

Russell Chatham: In defense of difficulty

When I met him for this interview, Russell Chatham—painter, printmaker, author, fisherman and restauranteur—gave me a short piece he wrote titled, “Advice . . .