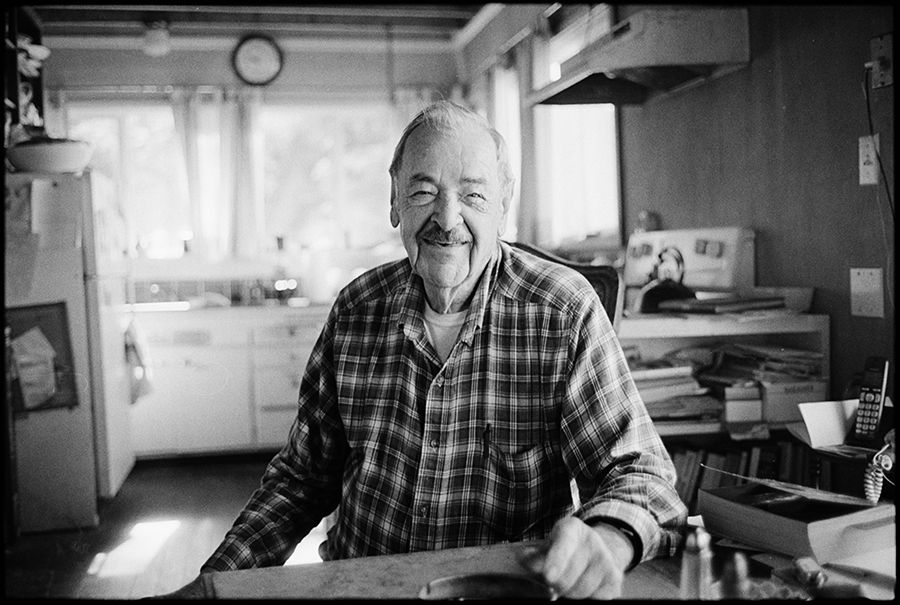

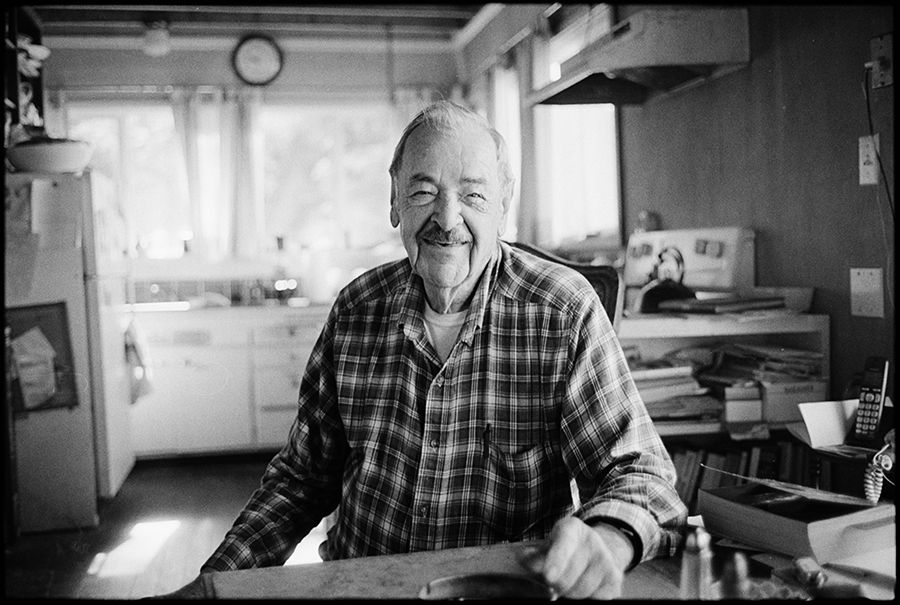

Paul Elmore was born in Petaluma and was a student and then a professor of sociology. He was president of the East Shore Planning . . .

Paul Elmore on sociology, isolation and life in Marshall

Paul Elmore was born in Petaluma and was a student and then a professor of sociology. He was president of the East Shore Planning . . .