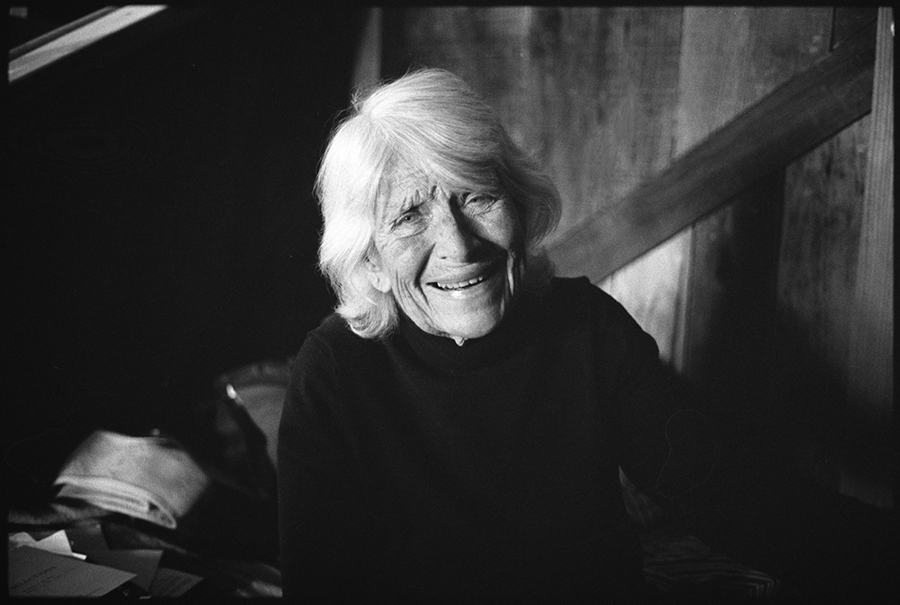

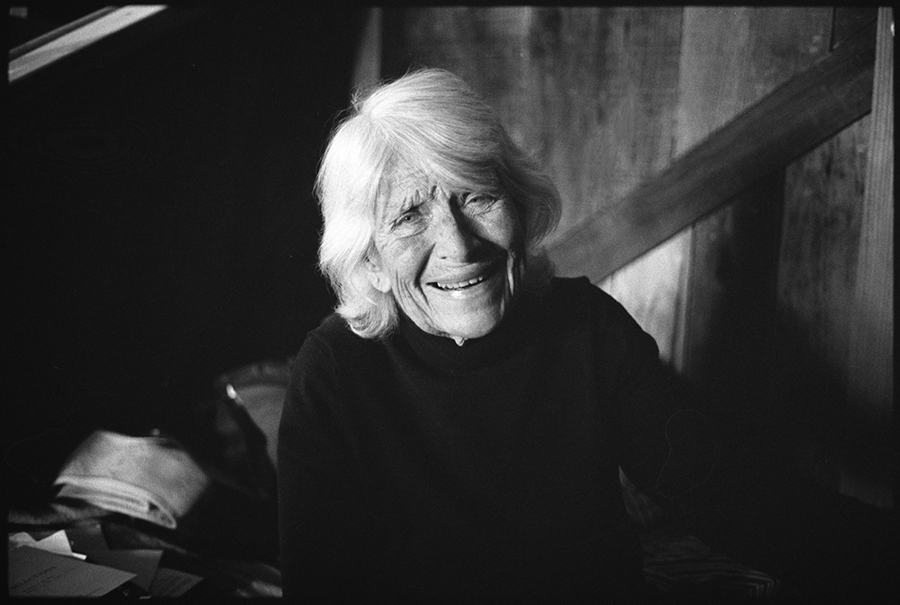

Mary Fuller McChesney is a sculptor and a writer. At age 93, she has written extensively about the arts, and her sculptures exist in parks . . .

Mary Fuller McChesney: Not at all intimidated!

Mary Fuller McChesney is a sculptor and a writer. At age 93, she has written extensively about the arts, and her sculptures exist in parks . . .