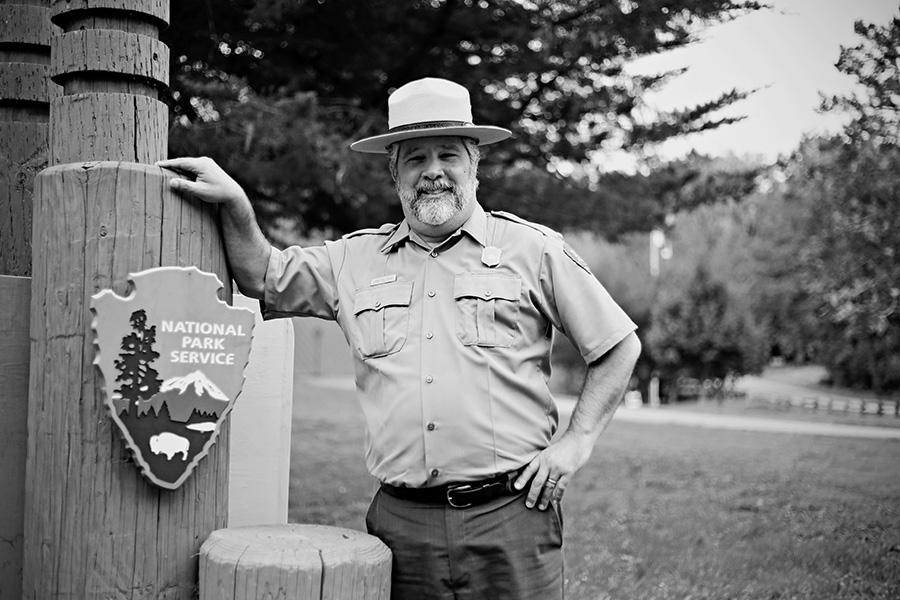

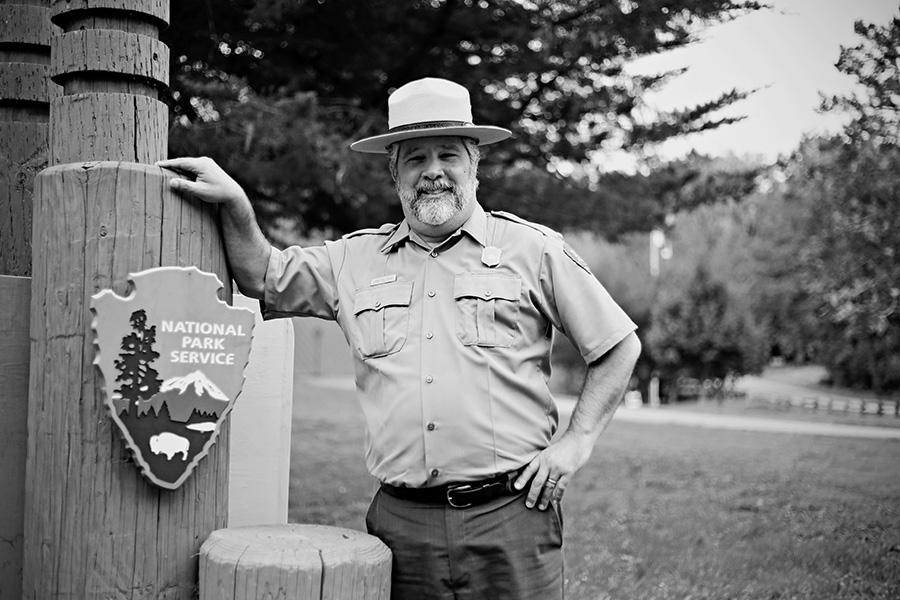

For nearly four decades, John Dell’Osso has been an integral part of the Point Reyes National Seashore. As the park’s chief of . . .

Longtime park chief to retire

For nearly four decades, John Dell’Osso has been an integral part of the Point Reyes National Seashore. As the park’s chief of . . .