Every Tuesday morning at the Woodacre Country Market & Deli, the Gangsters meet for a morning klatch. They are painters, artists, sculptors and photographers . . .

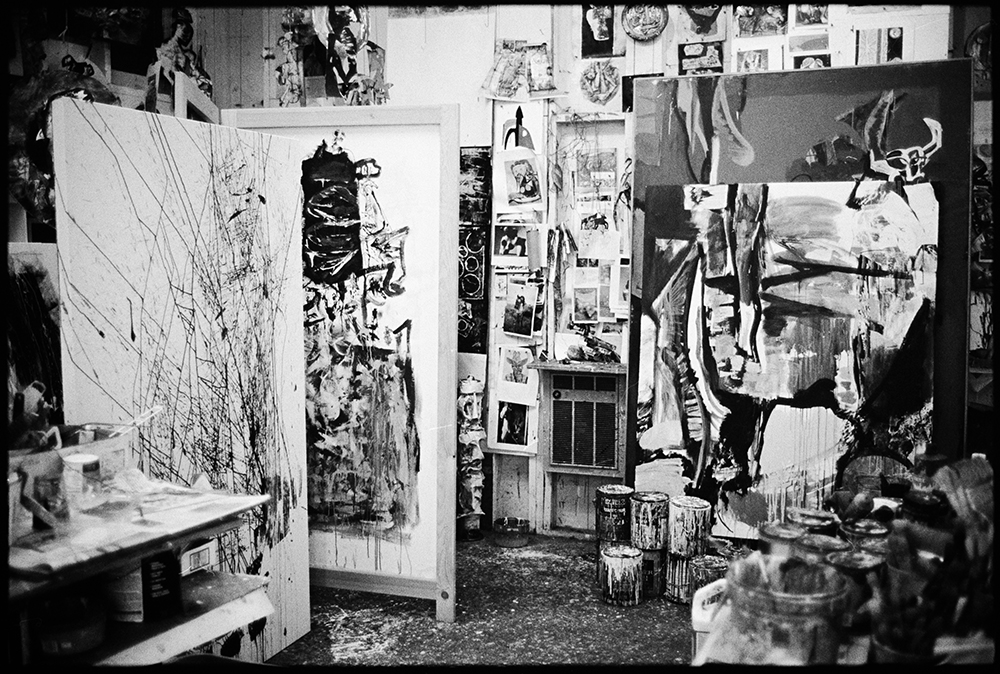

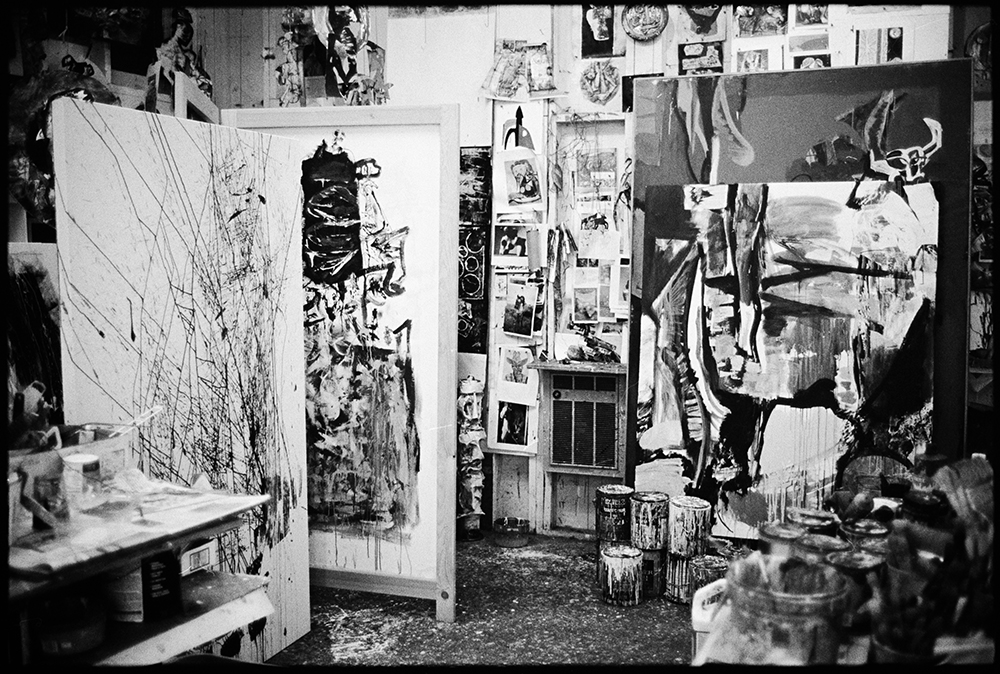

Harry Cohen: A life in service to abstract art

Every Tuesday morning at the Woodacre Country Market & Deli, the Gangsters meet for a morning klatch. They are painters, artists, sculptors and photographers . . .