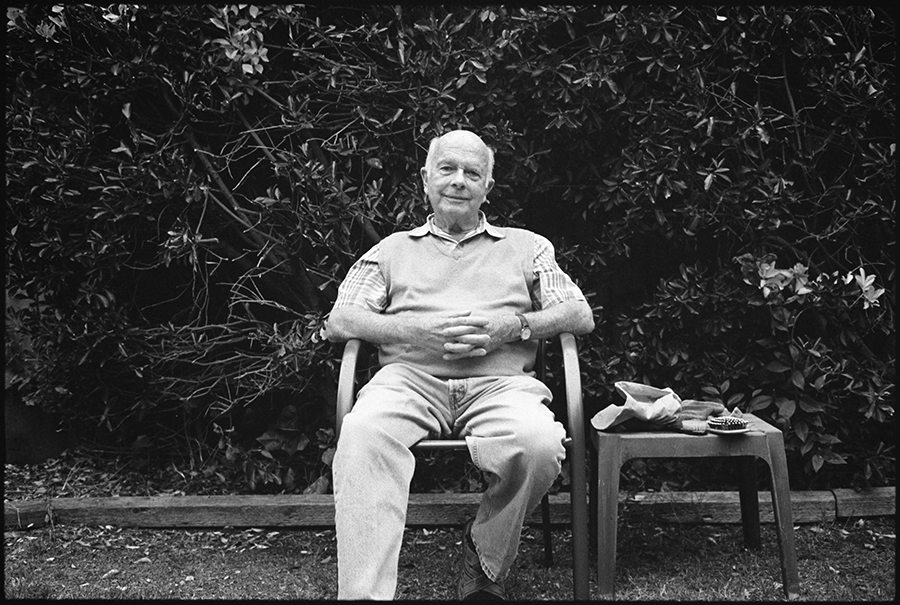

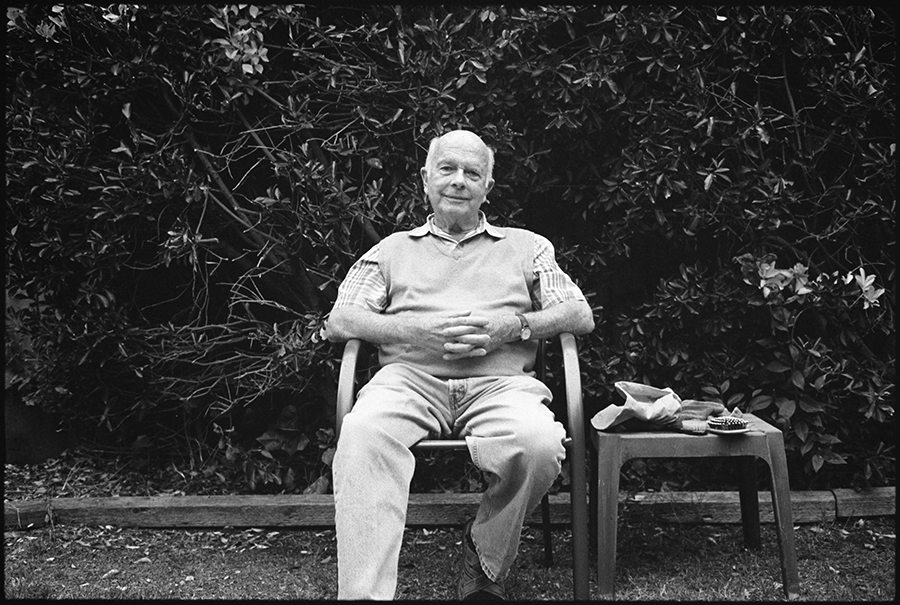

Hans Angress has many stories to tell, from surviving the Holocaust to helping build the Marconi Conference Center from the ashes of Synanon. But . . .

Hans Angress on early dairy farming on Tomales Bay

Hans Angress has many stories to tell, from surviving the Holocaust to helping build the Marconi Conference Center from the ashes of Synanon. But . . .