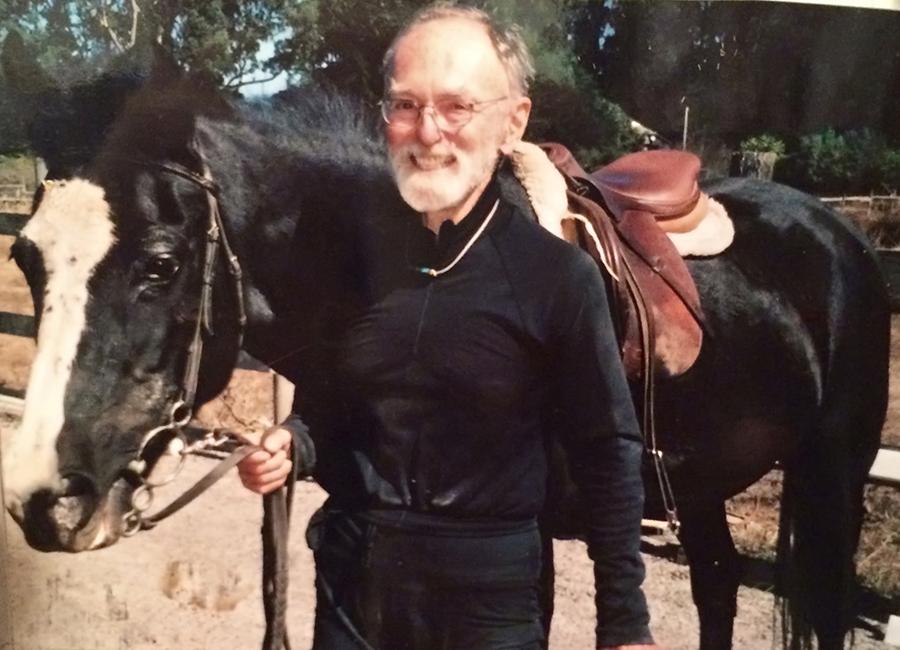

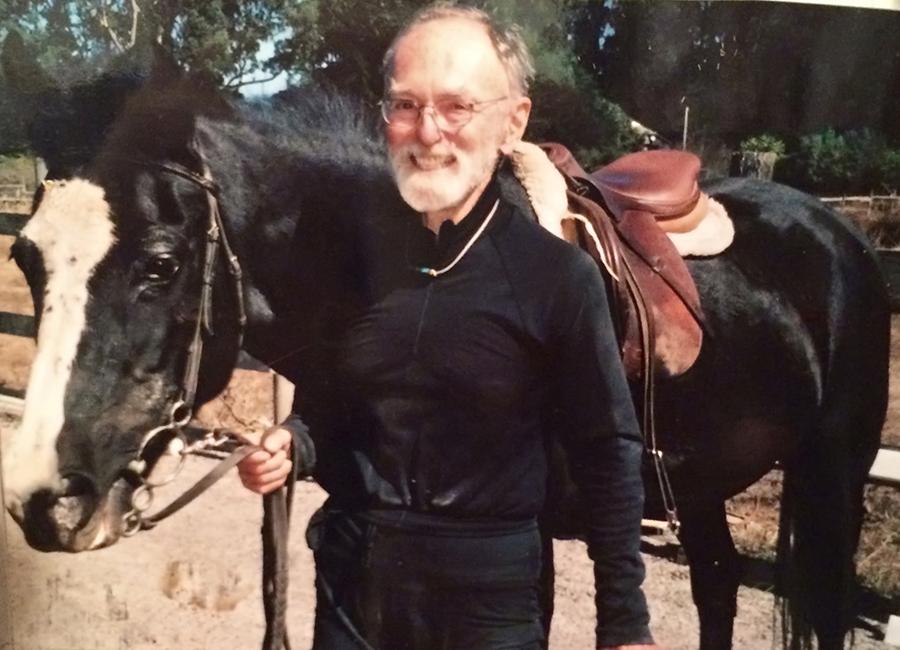

Alan Margolis, an obstetrics and gynecology doctor who championed female reproductive rights, advocated for family planning overseas and explored the seashore trails atop his . . .

Alan Margolis, global advocate of family planning, dies at 90

Alan Margolis, an obstetrics and gynecology doctor who championed female reproductive rights, advocated for family planning overseas and explored the seashore trails atop his . . .